Corresponding Author: 1Ruware Primary School, P.O. BOX 758 Marondera, Zimbabwe

2Zimbabwe Open University, Mashonaland East Regional Campus Department of Teacher Development, P.O. BOX 758 Marondera, Zimbabwe

DOI: 10.55559/sjahss.v1i03.15 Received: 25.01.2022 | Accepted: 28.02.2022 | Published: 31.03.2022

ABSTRACT

The study investigated the proliferation of unlicensed ECD (Early Childhood Development) Centres in Marondera Urban Ward 4. A sample of ten unlicensed ECD operators was drawn from a population of forty unlicensed ECD operators. The study was prompted by the high proliferation rate of the unlicensed ECD Centres in Marondera Urban Ward 4 for the past five years. Self-administered questionnaires were used to collect data from the unlicensed ECD operators. Interviews were used to collect data from Marondera Urban Ward 4 councillors and Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education (MoPSE) officer at Marondera MoPSE provincial offices. The data was analysed and presented in tables, charts and narratives. The results show that the councillor and the MoPSE were aware of the problem of the proliferation of unlicensed ECD Centres in Marondera Ward 4. The findings ECD business was dominated by women in Zimbabwe and no wonder why women were running the majority of unlicensed ECD Centres in Marondera Urban Ward 4. Women are perceived as the gender that was afraid to commit offences or crimes, but results show that they were bold to commit offences. Due to the harsh economic environment in Zimbabwe, women and men were alike in committing offences to provide for their families and survivors. Operating unlicensed ECD Centres was operating an informal business. The economic environment, personal motivation, the ease with which the ECD Centres could be established, and the relaxation of law enforcement agents were the main drivers of the proliferation of ECD centres in Marondera Urban. The study recommended that MoPSE and other stakeholders in the registration of ECD centres should amend the current ECD Centre registration policy and procedures to suit the current economic environment without compromising the health and safety of the ECD pupils. The government should give incentives to registered ECD Centres that may motivate unlicensed ECD operators to get licensed. The MoPSE and local authorities should involve ECD operators when formulating policies.

Keywords: Proliferation, Unregistered ECD Centres, District

The Early Childhood Development centres need to be operated in ways that satisfy the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education requirements. The purpose of Early Childhood Development is to develop young children’s minds, bodies, and emotions and produce individuals who are self-directed and lifelong learners. The state’s role is to design policies that reflect a developmental orientation.

Paull (2014) asserts that regulation of childcare quality can influence quality choices and facilitate the use of childcare by guaranteeing a minimum quality level when parents cannot directly observe or judge quality. In the UK, regulation is critical since it can raise the cost of childcare and may inhibit provision. To be efficient, regulatory requirements should be matched to quality improvements and the cost of evidencing compliance should be as low as possible. Is this the case in Zimbabwe?

Private Schools Policy and Procedures Manual (2013) proffers that to operate in Ontario legally, Canada, all private schools are required to submit a Notice of Intention to Operate a School (NIO) and failure to comply with their legislative requirement is an offence and this may result in a fine of $50/day for every person involved in the management of the school. In November 2011, the government ordered unregistered ECD centres to register, but a subsequent random survey by The Herald showed that many were still to comply. If this is the case in Zimbabwe, what is being done? However, in Europe, concerns have been raised that registration and other regulation have raised the costs of childcare and affected affordability (Department for Education, 2013b). Indeed, in Europe, there has been a recent shift towards reducing regulatory requirements, including an enhanced focus on learning and development in the revised Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) framework and a proposal to remove learning requirements for school-age childcare. All these efforts are being made to improve efficiency in the monitoring and enforcement of quality standards.

State of education in Africa Report (2015) postulates that the number of private schools across Africa for primary and secondary education continues to rise. In a UNESCO survey of 25 African countries between 2000 and 2008, private schools increased from 9 per cent to almost 10 per cent. The rise in private schools should not be seen as unfavourable but instead as a viable alternative to a failing public education system. However, these preschool centres should also be required to fulfil national policy, norms and standards on the provision of the ECD programme.

In South Africa, Child Care Act, 1983, section 30(2) states that a place of care must be registered, and no child may be kept in an unregistered place of care (except for places of care maintained and controlled by the state). Section 30(6) of the Act indicates that any person who fails to comply with the provisions and requirements for the registration of places is guilty of an offence. This means that places of care that are not registered are illegal, and the persons operating them can be charged with an offence (Guidelines for Early Childhood Services, 2006). To what extent are these ECD operators aware of the registration process in Zimbabwe? What challenges are the ECD operators facing in having their ECD centres registered? Kenya Gazette Supplement, Senate Bills (2014) posit that a person shall not offer early childhood education services or establish or maintain an education centre unless such person is registered in accordance with the country Education Board. Again, section 76 of the Basic Education Action of 2013 provides that a person shall not offer basic in Kenya unless that person is accredited and registered as provided for under the Act (Registration Guidelines for Alternative provision for Basic Education and Training, 2015).

In Zimbabwe, many children are not being catered for by the Ministry, hence the mushrooming of private ECD centres that are registered, and some are not registered. According to the Zimbabwean Education Amendment Bill, 2016, nursery schools must be written, and inspection will be provided at all reasonable times to ascertain compliance with this act. Therefore, this implies that all the private ECD centres are expected to be registered. Is this the situation in Yellow City, Marondera urban? This study got all the answers to these questions. In Zimbabwe, in its endeavour to fully implement the recommendations of the 1999 Presidential Commission of Inquiry into Education and Training (CIET), the Ministry of Primary and Secondary introduced several policy guidelines to address the Early Childhood Developments requirements. These include Statutory Instrument 106 of 2005, which stipulates the registration of early childhood centres and Principal Director’s Circular number 26 of 2011 on strategies to curb the mushrooming of unregistered ECD centres.

Statutory Instrument (SI) 106 of 2005 provides the regulations for establishing early childhood development centres, registration of these centres, cancellation of registration and the prohibition against conducting an unregistered early childhood development centre. With regards to these policies in place, this study seeks to analyse the factors influencing the proliferation of the unregistered ECD centres in Yellow City Marondera Urban in Mashonaland East province of Zimbabwe. Are these ECD operators aware of the ECD registration process in Zimbabwe?

A research carried out in Mutare District by Chiparange (2016) revealed that some ECD operators are not aware of the registration procedures, and the research carried out in Zengeza, Chitungwiza by Chitando (2018) shows that the ECD operators are aware of the registration process, but they do not meet the requirements. What is the situation in the unregistered ECD centres in Ward 4 Marondera urban District? The study found out what is happening in Ward 4 Marondera urban regarding ECD registration.

From a global perspective, international, regional and national levels, there are various causes for the proliferation of unregistered ECD centres. A summary of these challenges calls for this current study to critically analyse them and unearth how different ECD centres override some specific challenges supporting the national policy of developing the whole child.

The Herald, 23 April 2012, states that according to the Ministry of Education, Sport, Arts and Culture, there were 4908 unregistered private ECD centres and 3190 registered ones. In this manner, the researcher supposes that it might be difficult for the government to monitor the activities of the unregistered preschools. As a result, many children spend the more significant part of their early years in those unregistered preschools, which may negatively affect their development. The National Institutes of Health, The NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (2012) cited in Workman and Ullrich (2017), state that an estimated 6 million young children are enrolled in childcare, early learning programs. People who work in them have a critical role in child development- a role that compliments parents.

The main problem for this study is that not all learners are absorbed in primary school, hence the mushrooming of private ECD centres which are not registered but are offering services to the learners. As outlined in the background of the study, the Government of Zimbabwe developed the ECD national programme and specified how it should be implemented in line with international guidelines (Mugweni & Dakwa, 2013). Hence the thrust of the study was to analyse the factors influencing the proliferation of the unregistered ECD centres in unregistered ECD centres in Ward 4 Marondera Urban, Mashonaland East Province, Zimbabwe.

The following research questions provided a specific research guide to the data collection process:

4.1 Challenges faced by ECD operators or caregivers in registering their ECD centres

Strydon (2014) surveyed challenges faced by caregivers in registering their ECD centres in the Kabondo District of Zambia and found that there is a delay in reporting centres caused by the slow process of approving rezoning applications. He also indicated that the municipality faced a backlog of thousands of rezoning applications for ECD centres. In response, the Executive Mayor committed to investigating the status quo to craft a solution in the coming months. The Metro’s City Planning Department was also present to take note of concerns and outline their requirements for rezoning applications. What about the caregivers in Ward 4 of Marondera Urban District in Mashonaland East Province of Zimbabwe? Are they facing the same challenge?

Takafere (2016) investigated challenges faced by ECD operators in registering their ECD centres in the Matungulu sub-Country, Kenya, and found that infrastructure is one of the leading challenges of ECD centres not becoming registered or having substandard performance. Many centres function without the basic amenities of electricity, running water, or sanitation. Eric Atmore, Director of the Centre for Early Childhood Development, explained that a nationwide ECD audit in 2000 showed that 8% of ECD centres in South Africa do not meet the basic infrastructure requirements set by the Department of Education (Atmore, 2013). Lack of infrastructure presents significant safety risks and health code violations and causes poor service quality. The Department of Social Development does not provide a subsidy for physical building improvements or renovations. The informal settlements in need of ECD often do not have access to essential infrastructural services. Therefore, communities have the burden of paying for costs associated with building and/or renovations (Atmore et al., 2012) and providing basic amenities. Are the ECD operators in Marondera Urban District experiencing the same?

Research carried out by Owusu (2019) at Kiambu Country in Kenya indicated that having a skilled ECD practitioner in the workplace was not heavily regarded in the past, but it is slowly becoming a necessity. ECD service researchers’ study in the Western Cape showed that only 47% of the practitioners responsible for older children (3-5 years) had any ECD qualifications (Atmore, 2013). The Department of Social Development has set minimum standards for ECD teachers and caretakers. Today, ECD practitioners must obtain training as ECD educators (ECD Level 4, Further Education and Training Certificate) (DSD, 2015). This training provides essential skills to improve the quality of ECD services offered for the development of young children. Do the caregivers in Marondera urban face the same challenges in registering their ECD centres?

Camfield (2017) aimed to assess challenges faced by caregivers in registering their ECD centres in South Africa. He found out that ECD centres’ regulations in South Africa pose many challenges for centres throughout informal settlements. In his research, he pointed out that the biggest problem with the registration process is the cost to register. Many of these centres trying to start up and operate in very low-income areas cannot afford these fees and therefore fail to register, leading to them not meeting government regulations. He further outlines that other regulations are not feasible in certain informal settlements, such as available (safe and enclosed) outdoor play areas for the children. The requirements are two square metres per child. Many of these settlements are so dense with structures that this is not an option. Again, that centre would fail to meet the regulations and therefore fail to register as an early childhood development centre. For centres in informal settlements getting reported, there needs to be some modification of the governmental regulations to ensure these centres have the chance to become formal ECD facilities. Is this the same situation in Ward 4 of Marondera urban District in Mashonaland East Province of Zimbabwe?

4.2 ECD Registration Procedures

A research carried out by Diga (2016) in South Africa on ECD registration procedures indicated that after consultation with a service provider, caregivers needed to communicate with the various City of Cape Town local government departments to submit and obtain the following:

His research study points out that once all these steps have been completed, the service provider will deliver the complete portfolio of evidence to DSD for approval. If approved, a certificate will be provided, and registration will be granted as a Partial Care Facility valid for five years. If not, all steps are completed satisfactorily. Registration may be given conditionally (suitable for two years). Those conditions must be met within the stipulated period to gain complete registration. Once registration has expired, applicants will be required to follow the same process described above to renew their registration.

Diga’s research also indicated that caregivers should submit these clearance certificates and the supporting documents listed on the Checklist to the CECD Registration Team once all relevant clearances have been obtained. The CECD Registration Team will then visit the ECD centre to conduct a final assessment to assess whether:

Therefore, the above research findings are the registration procedures in South Africa; hence, this research study seeks to investigate as to the registration procedures in Marondera Urban District in Mashonaland East Province of Zimbabwe, and the researchers want to see if it is the same as of South Africa since these two are different countries with different governments.

4.3 Measures that are put in place by responsible authorities to ensure the registration of ECD centres

Another research carried out by Mthembu (2018) in South Africa, which set out to examine measures put in place by responsible authorities to ensure ECD registration, indicated that CECD has a group of ECD assistants that visit ECD centres in their areas to assist with the registration process. The findings of Mthembu’s research also points out that CECD also has an ECD assistant based at the offices in Claremont, with whom caregivers can contact to set up an appointment for assistance or delivery of documentation for their portfolio. Does the Zimbabwean government make any efforts so far?

The research findings of Mthembu (2018) indicated that before 1 October 2017 and the involvement of service providers, the Department of Social Development was responsible for the entire registration process of the caregivers in South Africa. However, there was insufficient capacity in the department, and thus there were significant delays in registering ECD centres. To reduce this backlog, service providers (like CECD) were brought in due to their existing relationships with ECD centres, their expertise in the field and their capacity to efficiently work through registration with centres. Is this what is happening with the responsible authorities of Marondera Urban District in ensuring ECD registration?

4.4 Strategies to promote ECD registration

According to the research carried out by Strydon (2019), in South Africa, on measures to promote ECD registration, only 30% of centres in Cape Town were registered, which leaves more than 2000 unregistered. Early childhood development is recognised as the foundation for success in future learning. Quality early learning programmes prepare children for adulthood, providing them with the necessary opportunities for social, cognitive, spiritual, physical and emotional development. These programmes assist in laying the foundation for holistic development while cultivating a love for lifelong learning.

The research study of Strydon (2019) outlines many challenges facing the ECD sector, notwithstanding the progress made in early childhood development since 1994. Children in South Africa still face significant challenges, including infrastructure, nutrition, ECD teachers, institutional capacity, and funding. Because of this, the City of Cape Town is processing ECD compliance applications online in the future, making it easier for centres to comply with regulations. Can the responsible authorities in Marondera Urban District undertake this as well to promote the registration of ECD centres in Marondera?

The research carried out by Strydon (2019) in Cape Town, South Africa, set out to examine measures to promote ECD registration, and the findings indicated that the online tool that has been developed sees staff members uploading all an applicant’s information in a single visit to their local Social Development and Early Childhood Development office. From there, the relevant inspections for fire safety and health compliance and compliance with building regulations are being coordinated. Applicants are being kept abreast of developments via SMS and email. Does the government make any efforts so far?

The research findings also pointed out that the responsible authorities are constantly looking at how they can improve the customer experience, and this online system certainly checks all of the boxes. Over the years, it has become apparent that compliance is a bridge too far for many unregistered ECDs, including the onerous task of going about the various steps required (Takafere, 2019). Their Social Development and Early Childhood Development Department has worked hard to close the gap, and hopefully, this technological advancement will see more unregistered ECDs apply to change their status. This interface streamlines ECD centre registration and enables the centres to access critically needed funding, food support and administrative support. Also, the department conducts regular surveys on registered and unregistered centres, constructs ECD facilities that meet all the requirements and offers training and capacity building with ECD practitioners, caregivers, and parents. Is this the same case in Marondera Urban District?

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

5.1 Research Design

The research design adopted for this study was the case study design. A case study is a method for learning about a complex instance based on a comprehensive understanding of that instance obtained by extensive descriptions and analysis of it taken as a whole and its context (Mertens, 2005). Accordingly, the case study design focuses on one phenomenon, area or individual, which the researcher selects to understand in-depth regardless of the number of sites participants or documents for a study. A case study may be a person, a family, a social group, a social institution, or a community (Creswell, 2014). Using a case study in this research study was to help expose the factors that influence the proliferation of the unregistered ECD centres, specifically in Yellow City, Marondera Urban. The case study thus provided a detailed understanding of the views voiced by participants, who included ECD operators, the ward councillor and the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education Officer in their specific situation.

5.2 Research Instruments

In this study, two research instruments were used. These are interviews and questionnaires. Fox and Bayat (2007) recommend using more than one research instrument to counteract bias than if the researcher uses are research instrument for data collection. Questionnaires were administered to ECD operators while the Councilor and the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education Officer were interviewed. The researcher made use of the questionnaires for several reasons. They were viewed as the most affordable way to gather a lot of data within a short time. The researcher also considered them practical. Questionnaires also offered respondents flexibility as they provided a wide range of answers to questions. Questionnaires were responded to at the respondents` own pace and time, giving them the flexibility to look at the whole instrument carefully before committing themselves to the contents. The researcher also had to follow up on specific points at any other moment on the questionnaires.

On the other hand, interviews permit face-to-face contact with the respondents, and it allows the interviewer to explain or clarify questions, thus increasing the likelihood of valuable responses (Fretchling & Sharp, 2013). Structured interviews were used in this research. The respondents, the councillor and the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education Officer in Marondera Urban were free to ask questions.

This study was concerned with the ten selected ECD centres in Yellow City. A total population of 12 was of interest to this study. The ECD centres had 10 ECD operators, one ward councillor and 1 MoPSE Officer, adding 12 prospective respondents. The sample is the group of people you select to be in your study. The researcher selected 5 of the ECD operators, one councillor, and 1 MoPSE Officer out of the total population of 12 prospective respondents through a random sampling method. The sample accounted for 58% of the total population and thus was representative enough of the population (Leedy, 2012). Five out of ten ECD centres were 50% of the people, hence also being representative of the people of ECD centres. Therefore, results from these five could be generalised to the other centres.

Narrations and descriptive statistics such as tables, pie charts and bar graphs were used to present and analyse data. They are practical illustrations depicting relations and trends. Data was presented in themes emerging from the findings.

Table 1: Duration of Unregistered ECD Centres in Operation

|

Duration in years |

Number of respondents |

Percentage |

|

0-4 |

6 |

60 |

|

5-9 |

3 |

30 |

|

10 and above |

1 |

10 |

|

Total |

10 |

100 |

Findings show that most unlicensed ECD Centres in Marondera Urban Ward 4 have less than five years in operation. Only 10% of the unlicensed ECD Centres has been in operation for more than ten years. Maybe it is the operation of this unlicensed ECD Centre that encouraged others to start theirs. Marondera Urban Ward4 saw an increase of unlicensed ECD Centres being established in their Ward in the last five years.

A qualitative question was asked to determine what motivated the respondents to start these unlicensed ECD Centres in Marondera Urban Ward 4, and various responses were mentioned. The following were some of the responses:

I was motivated at the college to start an ECD Centre of my own than to get employed but was hesitant to do so because of the law until I found out that others were operating without licenses; I started assisting ECD pupils doing home-work, and I found out that I was good at teaching young children though I had no teaching qualifications just O’ Level. People in the neighbourhood admired my talent and encouraged me to set up an ECD Centre. I bought the idea and started teaching ECD pupils at the family home. The pupils would bring their food, toys and stationery and pay me for the service.

Due to unemployment, I decided to start an ECD Centre since I had attained a diploma in teaching Primary Schools specialising in infants. I found out that it was the only business easy to start with minor capital. The pupils would bring everything needed, and I would only provide knowledge and learning space.

I just discovered that others were earning money by running the ECD Centre, of which I felt I could do that, and I started mine, too, with the support of church members.

Three women in my neighbourhood and my two sisters left their children with me when they went to work, and they paid me. Other women in the area started calling me a pre-school teacher, and they would ask me to keep their children when they went out and collect them in the evening. I found out that I would make more money if I opened an ECD Centre, and I mobilised resources to set up a formal ECD Centre, but unfortunately, the requirements were beyond my reach. I began to run an unlicensed ECD Centre and employ ECD teaching assistants as the number of pupils increased.

According to the above narrations, the unregistered ECD operators in Marondera Urban Ward 4 are using substandard or below standard infrastructures in their ECD Centres. According to Atmore (2013) and Takafere (2016), this concurs with some ECD centres in South Africa and Kenya.

The respondents were asked if they were willing to formalise their operations, and 60% of the respondent said they were ready to standardise their processes. 40% of the respondents said they were unwilling to standardise their procedures.

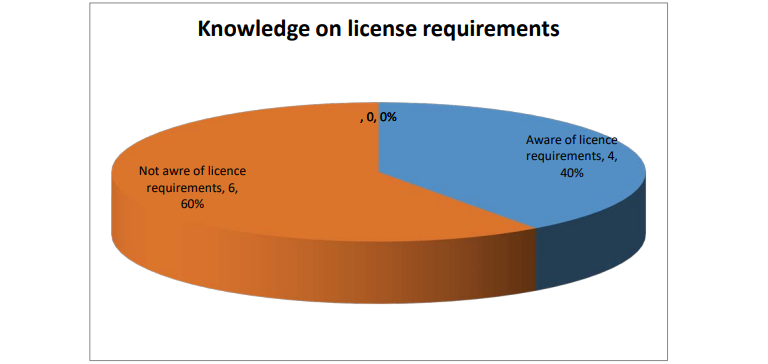

Figure 1: Knowledge on license requirements

The respondents were asked if they were aware of the licensing requirements of ECD Centres and 40% of the respondents said they were knowledgeable and 60% were not aware of the licensing requirements.

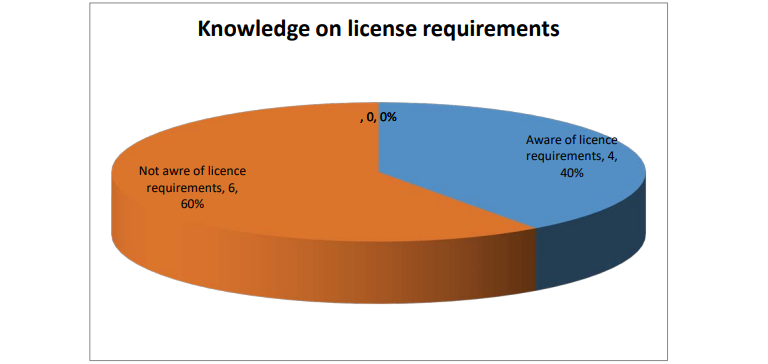

Figure 2: Respondents that attempted to get license for their ECD Centres

All the respondents never registered their ECD Centres and are operating illegally. The respondents were asked if they attempted to attain an ECD Centre driving license; only two out of ten respondents attempted to register. The other eight never tried to acquire permits for their ECD Centres, as shown in Figure 3. The reasons for not trying to write their ECD Centres by the majority of the respondents were not mentioned, and the researcher assumed that they knew they could not meet the requirements.

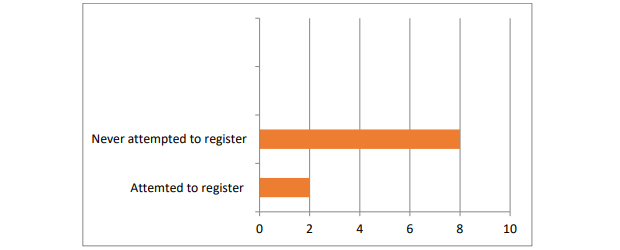

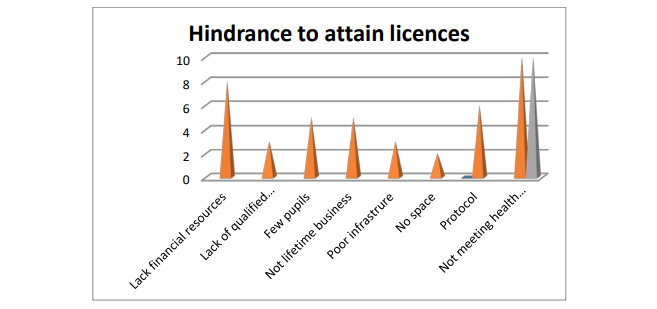

Respondents were asked what hindered them from registering at their ECD Centres, and various answers were given. The responses included lack of financial resources, lack of qualified teachers, poor infrastructure, few pupils, lack of space, and some mentioned that they are doing it on a temporal basis, so there is no need to waste money on something they will soon abandon and what they want to do in life when the economy improves. The findings on what hindered them from attaining licenses for their ECD Centres were quantified and presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Hindrance to attain licenses

The respondents mentioned more than one reason for not attaining a license for their ECD centres. Not meeting health requirements was the primary reason most ECD operators did not register their ECD centres. A lack of financial resources and protocol was the third reason for hindering ECD operators from attaining licenses. Few pupils and no lifetime business were fair reasons for not licensing their ECD Centres. Space was the slightest reason for not licensing their operations. Maybe others did not mention it because space has to do with financial resources and health requirements. Bureaucracy in the registration of ECD Centres is a challenge in Zimbabwe. Strydon (2014) surveyed difficulties caregivers face in registering their ECD centres in Kabondo District of Zambia and found that there is a delay in reporting centres caused by the slow process of approving rezoning applications. These delays may be caused by several offices to be visited before getting a license to operate an ECD Centre. The lack of qualified teachers was mentioned as a hindrance to the registration of the ECD Centre. This concurs with Owusu's (2019) posits that in Kenya, having a skilled ECD practitioner in the workplace was not heavily regarded in the past, but it is slowly becoming a necessity. The Department of Social Development has set minimum standards for ECD teachers and caretakers. Today, ECD practitioners must obtain training as ECD educators (ECD Level 4, Further Education and Training Certificate) (DSD, 2015). Camfield (2017) mentioned financial challenges as the main hindrance to registrations of ECD Centres in South Africa. His research results agree with this study in which economic resources is the second-highest hindrance to the registration and licensing of ECD Centres in Marondera Urban Ward 4.

The respondents were asked if they were arrested for operating ECD Centres illegally and what punishment they were given. All the respondents said they were not detained since they started operating their ECD centres illegally. Still, they contacted the law enforcement agents, who warned them to close their ECD Centres until they registered and licensed. Those warned did not complete their ECD Centres up to date, and the researcher collected this data from them. Those who got in conduct with the law enforcement agents were told that they would be fined if they continued their operations, and the fine, they were told, was not as much as to deter them from operating illegally.

Councillors are politicians and are responsible for their Ward developments; the respondents were asked if they were getting assistance from the councillor in connection with their ECD Centres. The majority said they never approached the councillor. Three of the respondents said the councillors were trying to give land to those who wanted to run ECD Centres and sign papers in the process of registering and licensing ECD Centres. Even though they knew the councillor's work, they did not approach him for assistance.

Respondents were asked if registering ECD Centre has advantages that outweigh the disadvantages of operating unlicensed ECD Centres; all the respondents said working at an unregistered ECD Centre had advantages over using a registered ECD Centre. They mentioned the high profit enjoyed by unregistered operators that were not shared with the government and other authorities involved in running ECD Centres. Some mentioned some hustles associated with licensed ECD Centres, such as regular inspections and renewal of licenses. They also said that you were put on the map of inspections once you got registered, and they knew where they could find you, especially these corrupt officials who took advantage of you. In other words, they meant that a licensed ECD Centre had more challenges than unlicensed ECD Centres.

Respondents were asked if there are associations that assist ECD Centres in Marondera Urban. If they are members of those associations, all the respondents said there are ECD associations in Marondera Urban, but only one respondent said he was a member. The respondents said the associations are responsible for capacity building, advocacy, and resourcing of the ECD sector. The researcher wondered why the respondents were not members of those associations.

The respondents were asked to give their views on what should be done to promote the registration and license of ECD Centres in Marondera Urban Ward 4. Various responses were provided and including the following:

The respondents' responses show that they were not happy about the laid-out processes of registration and licensing rules, and they feel the procedures are too strict and beyond their reach. They want the responsible authority and the government to revisit their processes and regulations to promote the registration and licensing of ECD Centres in Marondera Urban.

The Ward 4 Marondera Urban Councilor was interviewed, for councillors play a pivotal part in the development of their Wards as well as making sure that rules and regulations of the local authorities are maintained for they contribute to the crafting of local authority by-laws. ECD centre's establishment is part of the development in the ward and should be established according to the by-laws of the local authority. The councillor was asked five questions about the problem of proliferation of ECD Centre in Marondera Urban Ward 4.

When asked to comment on unregistered ECD centres in his ward, the councillor said there is a high proliferation of unregistered ECD Centres. It shows that the councillor was aware of the unregistered ECD Centres in his community. The councillor was asked what he was doing about the situation. The councillor said he had confronted some of the unlicensed ECD operators and had discussed the issue with them. The counsellor said he found out that these unregistered ECD Centres result from unemployment, and the operators were failing to meet the licensing requirements. The counsellor said he was trying his best to help the operators register their ECD Centres and get licensed. He also said he advised them to put their resources together register as a cooperative to be given land to establish a formal ECD centre, but his advice had been ignored.

The councillor was asked about his role in registering and licensing ECD Centres in Marondera Urban. He said his role is to recommend applicants for ECD Centre registration and empowerment and provide working space (land) for ECD Centres in his Ward. His answers show that the councillor is aware of his duties in connection with the establishment of ECD Centres in his Ward.

The councillor was asked what he had done to promote ECD Centre registration so far, and he said he had investigated the causes why ECD operators are failing to register their ECD Centres and had forwarded that to Marondera Urban Local Authority Board so that the issues be put in next board meeting agenda. He added that he had asked the Marondera Municipality to allocate land in every Ward to establish ECD Centres for the demand for ECD Centres had increased. The councillor’s answers to the question show that he is not only aware of his duties but also takes action to solve issues that arise in his Ward.

The final question was: What strategies do you think can be used to promote ECD Centre registration in Marondera Urban Ward 4? The counsellor said the government should provide incentives to registered ECD centres and punish the unlicensed ECD operators. After analysing their proposals, he added that land and financial resources should be provided to people who wish to establish ECD Centres. All formal primary schools must enrol Grade One pupils from only licensed ECD Centres. The counsellor said MoPSE and Local Authorities must revisit their prerequisite requirements for ECD Centres registrations rules and regulations and remove unnecessary rules that stand as barriers to ECD Centres’ registration without compromising ECD Centres’ standards. He also proposes a one-stop office for ECD Centre registration. The councillor’s answers to the question show that the councillor is aware of the challenges faced by ECD operators in trying to register their ECD Centres, and he does not want the present situation to prevail; hence he has strategies to overcome the current problems.

The MoPSE officer was interviewed on the proliferation of unlicensed ECD Centres because MoPSE is responsible for registering and licensing ECD Centres throughout Zimbabwe. Although other offices are involved, MoPSE has the final say on the issue of registration and licensing. The MoPSE officer was asked five questions concerning the proliferation of ECD Centres in Marondera Urban Ward 4.

The first question was why it was mandatory to register ECD Centres with the MoPSE. The following answers were given: An ECD Centre must be written so that the MoPSE may know the number of ECD centres in Zimbabwe and their physical locations and facilitate easy supervision of these ECD Centres to maintain quality and required minimum standards. The MoPSE officer added that quality ECD is fundamental to social and economic prosperity eliminating inequality and advancing child rights.

MoPSE officer’s answer shows that he was aware of the importance of registering ECD Centres in Zimbabwe.

The next question was on the requirements for registration in an ECD Centre. The MoPSE officer said that the registration of the ECD Centre was a long process that involves different ministries, and it begins with an application letter to start an ECD Centre with a detailed proposal to the MoPSE. He added that the requirements involved registrations with different boards that are concerned with ECD Centres, such as the registrar of companies, the local authority for lease or lease agreement and health inspections, Zimbabwe Revenue Authority (ZMRA) for tax clearance, National Social Security Association (NSSA), Ward Councilor and nearest Primary school head recommendations and fingerprints clearance forms. He handed me a printed requirement needed to have a fully licensed ECD Centre. The requirements required time and financial resources. The answer to the question showed that the requirements to acquire a license to operate an ECD Centre were cumbersome and expensive.

The MoPSE officer was asked to comment on the registered and unregistered ECD Centres in Marondera Urban. He said the number of registered ECD Centres in Marondera Urban is far less than the number of unregistered ECD Centres. He said there was a proliferation of unregistered ECD Centres in Marondera Urban. The answers show that he was aware of the expansion of unregistered ECD Centres in Marondera Urban, including those in Ward 4

The next question was: What do you think are the reasons for having so many unlicensed ECD Centres in Marondera Urban?

The MoPSE officer said the main reason there are unregistered ECD Centres in Marondera Urban is that they do not meet all the registration requirements. He added that most ECD Centres operate backyards in residential houses, which the MoPSE does not approve. The ECD Centres may work in residential homes, but a process to change the original use of the stand must be done first by the local authority, followed by health inspections.

The final question was on what should be done to promote the registration of ECD Centres in Marondera Urban, and the MoPSE officer said the unregistered ECD Centres should be closed. The operators should pay heavy fines for their illegal operations. He said unregistered ECD Centres should not compete with registered ECD Centres and be left like that; punitive measures should be taken. He added that the registration procedures must be reviewed to not be cumbersome and expensive without compromising the ECD Centres standard. He said primary schools should enrol pupils from registered ECD Centres only. The answers from the MoPSE officer show that he is aware that the registration process is expensive and it is a long process with unnecessary things are done during the process. His answers also show that he was hard on unregistered ECD Centres. Instead of giving incentives to promote the registration of ECD Centres, he prefers punishing them.

The study made the following conclusions:

Because of the above conclusions, the researcher made the following recommendations:

REFERENCES