1,4Ancient Indian History, Culture & Archaeology, Madhav University, India

2Ancient Indian History, Culture & Archaeology, APS University, India

3Ancient Indian History, Culture & Archaeology, JRNRV University, India

DOI: 10.55559/sjahss.v1i12.68 | Revised: 22.12.2022 | Accepted: 31.12.2022 | Published: 03.01.2023

ABSTRACT

This research paper intends to bring forth the forgotten treasures of Vasantgarh, enveloping the tangible and intangible heritage of the region, especially focusing on the Art and Metal industry and their relationship with trade and trading networks that developed in the era of the ancient city of Chandrawati and their connection with other trading centres of Rajasthan State & the border area of Gujarat State, the route being a part of the Silk-road trade route of world history.

The gathered data discloses the rich activity of art trade networks of Sirohi, the Western Indian Bronze School of Art and the area of Vasantgarh. The research paper includes a field survey and the collection of quantitative and qualitative data, which floodlit the immemorial history of the Rajputana State (Rajasthan) especially referring to the early traders of Sirohi who controlled the export and import of goods in the Medieval era.

Vasantgarh, an ancient smelting site of Sirohi was an important centre for the mining and smelting of copper. The evidence of a strong smelting industry is backed by the discovery of abounding dumps of smelting slags. The alloy sculpting arts of Vasantgarh employs one of the oldest methods for metal binding still in use: the Lost Wax method. The other important metal-joining techniques require a deep archaeometallurgical study-for example, riveting, brazing, brazing flux, welding and soldering. The Vasantgarh School of Art is connected with the industrial production of finely crafted alloy metal sculptures that gleam like gold. The 240 sculptures, related to Jainism, were recovered from an unauthorised treasure hunt. The prosperous city owes its design to the region's rich trade, which is why it is carefully guarded with a number of towers and walls. The city had been fortified in order to protect against robbers and other kingdoms who might pose a threat.

Keywords: Sculpture Arts, Brass Idols, Silk Route, Trade, Vasantgarh, Ancient Metallurgy

|

Electronic reference (Cite this article): Talesara, P., Bahuguna, A., Saini, R., & Thakar, C. The Abandoned Treasures of Vasantgarh: Art, Metal Industry and Trade. Sprin Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, 1(12), 01–17. https://doi.org/10.55559/sjahss.v1i12.68 Copyright Notice: © 2022 Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license. |

Rajasthan is India's largest state, and it has nine distinctly different cultural regions. Each region has its own unique history, heritage, and traditions related to art, archaeology, and defense. Rajasthan is a land of kings - the kings who have ruled this state have left a lasting legacy that can be seen in the many beautiful architecture and archaeological sites found here. (Talesara, Bahuguna, & Thakar, Archaeology of Bandiyagarh, Sirohi, Rajasthan, India, 2021, p. 1). Sirohi lies between latitude 24 degrees 22’ and 25 degrees 16’ N., and between longitude 72 degrees 22’ and 78 degrees 18’ E, with an area of 1964 square miles (Talesara, Bahuguna, & Thakar, Archaeology of Bandiyagarh, Sirohi, Rajasthan, India, 2021, p. 1).

In ancient times, the kingdom of Sirohi was known for Arbuda Parvat (Mt. Abu Kingdom or Arbudanchal) and the deserted capital city of Parmars- Chandrawati- lying in the Godhwar region of Sirohi in Rajasthan state of India. The term Godhwar stands for cradle (Talesara, Bahuguna, & Thakar, Archaeology of Bandiyagarh, Sirohi, Rajasthan, India, 2021, p. 1). The rare art of Sirohi, now kept in the Jain temple of Chintamani in the city of Bikaner in Rajasthan state, envelopes the 1050 Jain images (paintings and sculptures) and precious idols made up of stone, gold & brass which were looted by Sultan Tursam Khan (one of the commanders of Mughal king Akbar) in AD 1576 from the shrines of Sirohi. In AD 1586, allying with Akbar, Rai Singh took over the artwork and finally donated these idols to the Bikaner temple. (Jain M. , 2019, p. 129).

The site of Vasantgarh is located in Pindwara Tehsil, on the West Banas River of the Sirohi district of Rajasthan state. The old names for the site, as known from various sources were, Basantgarh Vetaleara, Vatasthana, Vatanagra, Vata, Vatapura and Vasisthapura. This place is called Vata because there are a lot of banyan trees here. It was a popular belief in the eleventh century that Sage Vasistha, once had his hermitage under the banyan trees, where he erected the temples of Arka and Bharga, and with the aid of the architect of Gods-Vishvakarma- founded the city Vata, bedecked with ramparts, orchards, tanks and lofty mansions. The place was therefore called Vasisthapura, which with the elapsing time developed into a prosperous town as is clear from the ruins of the palatial buildings of the kings and the temple of different religions.

The inscription of Purnapala- Parmar king- found from the step-well of Vasantgarh informs that the area was also known as Vatakara or Vatapura (Talesara, Bahuguna, & Thakar, Archaeology of Bandiyagarh, Sirohi, Rajasthan, India, 2021, p. 6). The word “Vatapura” given by the Parmar clan explains the fort (Pura) built by them in the Vata (banyan) tree forest (Talesara, Bahuguna, & Thakar, Archaeology of Bandiyagarh, Sirohi, Rajasthan, India, 2021, p. 5). This shows that Vasantgarh was an example of Van-Durga and the Parmar dynasty was familiar with that tradition (Talesara, Bahuguna, & Thakar, Archaeology of Bandiyagarh, Sirohi, Rajasthan, India, 2021, p. 5). On the other hand, the term “Vatakara” is connected with the word “Akara” meaning an important centre of mines and smelting (Talesara, Bahuguna, & Thakar, Archaeology of Bandiyagarh, Sirohi, Rajasthan, India, 2021, p. 6).

Vasantgarh, the city of great antiquity must have been in existence long before the first half of the Seventh Century AD. In AD 625 it was held by Rajilla & his father Vajrabhata Satyasraya, both, a feudatory of the same king Varmalat from Bhinmal. King Rajila protected Mt. Arbuda and had his capital at Vasantgarh. The numismatic evidence found from Vasantgarh identified King Varmalat of Bhinmal/Shrimal, although his dynasty remains unknown due to the absence of sound sources. Later in AD 646, according to the Samoli inscription of Udaipur, king Siladitya ruled over Vatanagara (Vasantgarh).

Epigraphic sources of early medieval times acquaint us with the rule of various kings and dynasties over the concerned area, starting from the Parmars of Abu (AD 800-1270) who recognized the suzerainty of Chalukyas of Gujarat (AD 940-1244); in AD 1405 the Siranwa hills of Sirohi came under the Deora Chauhans of Nadol and in AD 1433-1468 Maharana Kumbha of the Guhila Dynasty was ruling over Vasantgarh and Achalgarh. The region was finally captured by the Deora-Chauhan in the fifteen century.

Metallic sculptures have been discovered from the later Gupta period (after AD 600) onwards, mainly from the western Banas valley of the Abu (Hooja, 2006, p. 138). No doubt Sirohi was a vital trade route between Gujarat, Agra and Arab, therefore mentioned by medieval travellers like Herbert, Olearius, Della Valle and Bernier (Malekandathil, 2016). During the Mughal period, there was sufficient traffic according to historian Elliot, and three trade routes existed from Ahmedabad to Ajmer namely: (i) the road passing through Medata (Medapata ancient name of Mewar), Sirohi, Pattan and Desa, reaching Ahmedabad, (ii) the highway from Ajmer to Ahmedabad passing through Medata, Pali, Bhagwanpur, Jalore and Pattanwal, (iii) the highway from Ajmer to Ahmedabad passing through Jalore and Haibatpur (Chandra, Trade And Trade Routes In Ancient India, 1977, p. 25).

The trade networks with ancient cities like Kutsapura, Chandrawati, Vatapura and Brahmana lying in the Sirohi district of Godhwar region and other trading cities like Pali and Bhillamal located in the Gujarat State and Marwar region played a crucial role in the development of the architectural style in Mt. Abu. The gem-stones and lapis-lazuli serve as some of the important evidence for economic trade and transport that connected the trade network from Afghanistan and some of the Middle-Eastern countries (J.S. Kharakwal, A.K. Pokhariya & Et. al., 2016). The discovery of gem-stones like carnelian and lapis-lazuli from the site of Chandrawati, located in a small town of the same name, is exemplary to the economic trade and transport and had been an important town centre for trade since the time of Parmars (Talesara, Bahuguna, & Thakar, Archaeology of Bandiyagarh, Sirohi, Rajasthan, India, 2021, p. 6). The textual source of Jinaprabhasuri (AD 1389) described Chandrawati as ‘full of wealth’ (Talesara & Bahuguna, Decoding of the Story Superimposed of Buddhist Sculpture unearth from Bharja and testifying its relation to this Silk- route area of Sirohi District, India, 2020b, p. 304) and the text Tirthmala of Megha (AD 1443) compared Chandrawati to the Golden City Lanka of Ravana (Jain K. , 1972, p. 345).

This research paper endeavours to focus on the artistic excellence, metal industry and trade networks that developed within ancient sites of Sirohi and their connection with other trading centres of Rajasthan & border area of Gujarat that established the link with the Silk-road trade route of the world history. Based on our previous research, the gathered data illuminates the trade relations of Sirohi, identified as the Western Indian Brass School of Art in Vasantgarh. The research raises a few questions to fully understand the mysterious role of fortified cities. For instance, what were the products and art quality that the contemporary small and large industries based in Sirohi were selling for wealth?

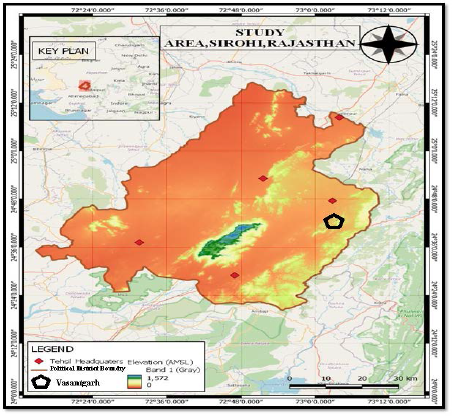

The archaeological research was done by gathering data and carrying out field exploration in order to obtain insights into the previously explored cities as well as new sites that are related to our studies. Various artefacts were collected for dating, after making assumptions based on observations about the material culture of these places. This process helped us determine a few dating points that were reached through extrapolation from the things we observed about this city's construction materials and style of art and architecture. Efforts were made to further improve and compile information through talks with the local community and conversations with a renowned historian. We have used specific technological applications, like AutoCAD, QGIS, Google Earth Pro, and Bing Map, which have helped us gather quantitative data related to GIS studies. We also had access to various other Geospatial programs which helped us pinpoint GPS locations for the site and trace MSL data for the location. Qualitative research includes collection of data from various libraries. These included "Sahitya Sansthan Shodh Pustakalya, Udaipur" and "University of Rajasthan, Jaipur". In addition, we used topographical sheets from "Survey of India" for reference during our pedestrian survey.

Figure 1: Map of Sirohi Showing the Location of Vasantgarh, created using QGIS Software

Vasantgarh is thought to be the dwelling of Sage Vasistha; today it only has ruins of the fort and temples. The inscriptions from the site date back to the 6th to late 11th century AD (Talesara, Bahuguna, & Thakar, Archaeology of Bandiyagarh, Sirohi, Rajasthan, India, 2021, p. 5). Some folklore are also prevailing in region that associated with Sage Vasistha (Talesara, Bahuguna, & Thakar, Archaeological Exploration of Defence Structures & Fortress City based on Ancient Folklore of Mount Abu, Rajasthan, India, April 2020, p. 99). Vasantgarh was rich in copper mines and in ancient times, it was used to manufacture bronze metallic sculptures which are exquisitely artistic, similar to the sculptures of Akota bronze of Gujarat (Shah, Akota Bronze, 1959, p. 2). The large numbers of copper slags found in Vasantgarh are evidence for the area being an important centre of copper activity (Talesara, Bahuguna, Mani, Khan, & Thakar, 2021, p. 130). 240 Jain brass & bronze idols recovered from an unauthorised treasure hunt justifies the importance of the metal art industry & also suggests its trade & commercial significance because the hoards were possibly a part of the art school workshop (Saini, Talesara, & Bahuguna, 2022, p. 27). Most of the 240 Jain idols are now kept in the ancient Mahavir Swami Jain Temple in Pindwara (Talesara & Bahuguna, Decoding of the Story Superimposed of Buddhist Sculpture unearth from Bharja and testifying its relation to this Silk- route area of Sirohi District, India, 2020b, p. 308).

Figure 2: Modern Extension near old mines, Mine 1(B) and Mine 2(A)

The survey guided us to a trail along the West Banas River, near the Amba Ji Temple, which was loaded with dumps of slags and raw materials on both sides of the river, indicating the smelting activity and in some places,we noticed large cavities in the ground. The path led up to a location where two copper mines were found at some distance. According to the locals, the antique mines were closed down when the upper layer was exhausted of copper; and probably began again later, when the old mines were drilled deeper to fetch more raw material. The information is backed by the evidence from the construction of the upper mine walls by older construction techniques using bricks and stones, which had modern cementing added to it later, making it more sturdy.

The large dumps of slags near the mines are a marker for in-situ smelting, which itself is an indicator of an old mining site, as modern-day mining is technologically far more advanced, having different processes of metal extractions performed by different bodies and not on the site itself.

Present Condition: when the site was surveyed, the mines were filled with water; walls were chipped and mine 1 [Figure 2 (B)] had scattered pieces of the broken roof.

3.1.2 Modern Mining for Cement production

Figure 3: Comparative study of old satellite views, showing the speed of mining extension

During the survey, the expansion of the modern mining and cement factory, near the Vasantgarh Fort, was brought to light. The visible white patch in the image above (Figure 3), is the area occupied by the mining of raw materials for cement factories located near the mines.

The image shows the distance of the mines from Vasantgarh Fort over the years- 1.44 km in 2006, 780 m in 2015 and 480 m in 2022. On average, it is expanding at a speed of 60 m per year and will reach the heritage site within 6 to 8 years.

3.1.3 Metal Art

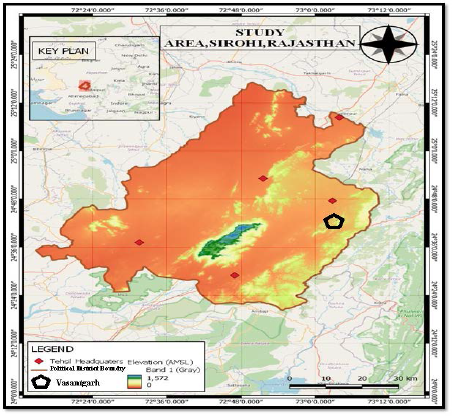

Figure 4: Jain Adinath Tirthankara (A) and Shantinath Tirthankara (B) retrieved from the ruined Jain temple, Vasantgarh; idols are now kept in Mahavir Temple, Pindwara, (Shines like Gold Brass Art)

The photographs shown above (Figure 4) are the two Tirthankara – Adinath and Shantinath- originally taken from the Mahavir Jain Temple of Pindwara on a special request from Jain Monk Munishwar Vijay M.S.

In the realm of Jain art, nothing is so far known which may be datable before the 7th century AD. These metal sculptures (figure 2) from Vasantgarh art school are in Kayotsarga pose (standing position), with the style of hair-slocks falling on the shoulders. The two sculptures are similar in casting, without bearing any marks or characteristics that may be used as a point of distinction, the only difference is the height- the Adinath sculpture measures about 42 inches & the metal pedestal is 10 X 14 X 10.5 inches, whereas, the Shantinath sculpture is 40 inches high with the metal pedestal measuring 14 x 12 x 15.5 inches (Shah, A Bronze hoard from Vasantgarh, 1956, p. 56).

Both the idols were cast & sculpted by the sculptor named Shivanaga who was elevated to the status of God Brahma (Pande, 1984, p. 86). The information is inscribed on the idol of Adinath Tirthankara which was identified by the temple Parishad and the idol of Shantinath has the inscription on the face of the pedestal, which was deciphered by an eminent historian, Gaurishankar Ojha. According to the inscription, the idols of the two Tirthankaras were offered by Yasodeva for the spiritual benefit of acquiring correct knowledge, right action and right faith; the date mentioned is 744 Vikram-Samvat (AD 687) (Shah, A Bronze hoard from Vasantgarh, 1956, p. 56).

Unfortunately, it is impossible to research or photograph all the other remaining sculptures from the 240-sculpture treasure. Due to religious sentiments and limitations, we are hereby attaching sketches of some sculptures from that hoard, ranging from 3 inches to 45 inches in size.

Figure 5: Photography is not allowed in Jain Temple; here are some sketches from Vasantgarh that showcase sculptures found during excavation.

Apart from the idols of the Tirthankaras, some of the other noteworthy sculptures exemplifying the impeccable aesthetic metal art of Vasantgarh are-

The Sculpture: the crown of the Devi is elaborate; holding a lotus stalk in her right hand and a manuscript in her left hand. It has a sun disc atop and a Makara head on either side (Pande, 1984, p. 86). The halos are in form of dotted rims (Pande, 1984, p. 86). Today this sculpture is kept in the Mahavira Temple of Pindwara but is worshipped as Chakreshwari Devi.

Gauri or Parvati (part of Shaivism) is shown with a bull and is speculated to date between the late 8th and 9th century AD (Pande, 1984, p. 86).

It should be noted that the sculptor was well aware of the canonical iconography as per Jain tradition, finding examples in Adinath Lanchan hair-locks falling on the shoulders, Parashvnath represented with seven hooded serpent- Shesh-naga (sacred serpent), Jain Sarasvati shown holding the Vedas. One of the most important things is the justification of the religious intent through the art, which is beautifully sculpted like the Makara-head (Kirtimukh) which is referred to as the face of glory.

It must be noted that in the Akota and Vasantgarh sculptures, the inner core is invariably allowed to remain intact and not be raked out since it provided a sort of reinforcement for the delicate parts in case of an accidental fall (Shah, Akota Bronze, 1959, p. 19). The art school of Vasantgarh sculpted these sculptures through the Lost Wax method with a heavy black core inside (Shah, Akota Bronze, 1959, p. 2). These sculptures probably contained inscriptions which mainly embody brief details of the donor (Shah, Akota Bronze, 1959, p. 2). The process of lost wax includes melting the metal and pouring the molten metal into the moulds. In the next step, the cooled clay mould is broken down to get the solidified metal sculpture from the inside, which is then subject to further processing and beautification (Shah, Akota Bronze, 1959, p. 18).

As already mentioned, Vasantgarh was an important centre for copper smelting as is evident from large-scale copper slags found at the site. It could be possible that the area was well-known for the copper mining industry before AD 625 as the earliest inscription of Vasantgarh (AD 625) refers to the name of the city Vatakara. “Vatakara” connected with the word “Akara” means an important centre of mines (Talesara, Bahuguna, & Thakar, Archaeology of Bandiyagarh, Sirohi, Rajasthan, India, 2021, p. 5). Vasantgarh played a significant role in the history of bronze/brass casting in Western India, the bronze hoard found in the cellar of the temple of Shantinatha was dispersed, but the main bulk went to the temple of Mahavira Swami, Pindwara. The bronze idol of Saraswati dated AD 650-75 and the earliest Jain idol Rishabhanath dated AD 687 speaks about the metal sculpture industrial activity in early medieval times (Chandra, Prince of Wales Museum Bulletin No. 11, 1971, p. 15). Late Smt. Amaravati Gupta used to have collections of some important bronze sculptures of Western India, later on; she donated them to The Prince of Wales Museum of Western India in Bombay (Chandra, Prince of Wales Museum Bulletin No. 11, 1971, p. 15). Amaravati Gupta asserted that these bronze sculptures belonged to Western Indian art school sites like Akota and Vasantgarh (Chandra, Prince of Wales Museum Bulletin No. 11, 1971, p. 15). The collection represents twenty-one bronze sculptures, nine sculptures belonging to Jain Tirthankara Parashvnath (23rd ford maker of Jainism) which shows that he was widely adored in Western Indian art school (Chandra, Prince of Wales Museum Bulletin No. 11, 1971, p. 15). However, the sculptures studied by Dr Shah (author of the book ‘Akota Bronze’) may have been possibly dispersed from the original Vasantgarh hoard.

Our team's XRF test on a sculpture shows that most sculptures are likely brass hoards, not only bronze hoards as suggested by previous scholars and in comparison, to Akota Bronze (Saini, Talesara, & Bahuguna, 2022, p. 34).

|

Figure 6: Bandiyagarh Brass Art |

The ancient site at Bandiyagarh was discovered by our team. It is only 10 km away from the site of Chandrawati (Talesara, Bahuguna, & Thakar, Archaeology of Bandiyagarh, Sirohi, Rajasthan, India, 2021, p. 7). A fortified settlement is located on a high and often strategically advantageous location atop a plateau with relative isolation surrounded by natural barriers. A well-fortified town wall surrounds the settlement ensuring its safety (Talesara, Bahuguna, & Thakar, Archaeology of Bandiyagarh, Sirohi, Rajasthan, India, 2021, p. 7).

A Jain sculpture of Parashvnath made of brass was discovered at the site, dated AD 1154 (Talesara, Bahuguna, & Thakar, Archaeology of Bandiyagarh, Sirohi, Rajasthan, India, 2021, p. 11). It was made with the same technique- the Lost Wax method. The idol has several riveting metal points, other than the main body, added to enhance the beauty of the sculpture; some of the minor riveting metals are quite precious and rare in nature. (Saini, Talesara, & Bahuguna, 2022, p. 33). The Zinc and Copper amalgam found in the main body is the primary cause for the sculptures shining brightly like gold, the sculpture's features are adorned with rare and precious metals, including Gold and Iridium. (Saini, Talesara, & Bahuguna, 2022, p. 33).

The sculpture's iconography features a seven-headed serpent, Srivastra (held holy gem on its chest), and an array of guardian creatures surrounding it. On the right side is a male Yaksha-Dharanendra, while on the left is a female Yakshni-Padmavati (Talesara, Bahuguna, & Thakar, Archaeology of Bandiyagarh, Sirohi, Rajasthan, India, 2021, pp. 11, 12). In our previous research paper (Talesara, Khan, & Thakar, An archaeological documentation and investigation on fortification discovered in the Aravalli range, Rajasthan, 2020, p. 291) we mistakenly assumed the lost part of Yaksha was a Chauri-bearer, but after comparing it with the Akota Jain bronze sculpture, we were able to identify it as a male Yaksha.

The Bandiyagarh sculpture of Parashvnath might have been manufactured by the Vasantgarh School of art / metal industry. This can be justified by its similar trademark of artistic beauty and features.

Figure 7: Front and Back side of Bronze Idol of Adinath, Ore Village, Sirohi,( Vikram Samvat 1515

In order to gain a deeper understanding of this art, we tried to study the sculptural art discovered by us earlier from the site -Ore (Talesara & Bahuguna, Archaeological Exploration of Sirohi District, Rajasthan, 2020a, p. 16). The date of the Ore bronze sculpture is inscribed as 1515 Vikram Samvat (Figure 7) which we discovered from Adinath Jain temple, Ore Village (Talesara, Ancient Defence Structures or Forts in Sirohi District, 2022). The attributes of the sculpture reflect similar characteristics as that of the Parashvnath idol (Figure 6), as some of the features appear to be of different metals put together to form a single body, probably used to enhance the beauty of the sculpture.

Though the Adinath sculpture belongs to a later period, the features of this sculpture are very similar to that of Vasantgarh from an earlier time, showing a possibility that this sculpture also belonged to Vasantgarh and the tradition of sculpting was followed even to the later dates.

During our exploration, we discovered sculptures built through beautiful glazed marble stone. These sculptures clearly show that the sculptor was well aware of Indian iconography because we see (a) Sheshsayi Vishnu, (b) A Sculpture of Brahma, (c) A broken sculpture of Navgriha and a sculpture of Malyudh (traditional Indian wrestling in a muddy stadium), (d) Colossal idol of Lord Ganesha (e) River goddess (Ganga & Yamuna) on Shiva Temple (f) Broken sculpture of Jain Tirthankara and Narsimhavtar of Vishnu.

The old idol of Sheshsayi Vishnu is kept in a ruined temple located near a step-well.

Sheshsayi Vishnu (Figure 8, sculpture of sleeping Vishnu), Iconography described:

It is a Narayana Vishnu sculpture having four arms with the second pair of arms adjoining the first one from the back. One hand to the front is shown resting on the chest, holding the Shankh (conch shell) while the other is holding the Sudarshana-chakra; one of the adjoining hands to the back is supporting the head, with the weapon Gada (mace) lying on the arm, whereas the other hand is shown horizontally straight, holding the Padma (Lotus). Lord Vishnu is seen seated in the Sharshaiya asana (reclining position), with the coiled serpent Shesh-naga. Lord Brahma can be seen emerging from the navel of Vishnu; and Goddess Laxmi is seated near the feet, pressing them.

The carved image of Bhu Devi is noticeable on both sides; features are damaged. Vishnu is surrounded by Vaisnavite devotees and Devgan (other deities) from the sky and downward groups of musicians and other Loka devotees.

Figure 8: Sculpture of Sheshsayi Vishnu at Vasantgarh

The tall-sized idol of Lord Brahma is now found near the Sun Temple. The earlier report tells us that temple was built in the same style of architecture as the Surya Temple of Vasantgarh ( Vijay Kumar, 1990, p. 14).

Brahma Iconography: The idol is shown standing straight with four heads (one head hidden at the backside), beautifully dressed in Indian attire. The sculpture is holding a Kamandal (water pitcher) which is damaged in one hand and a rosary in the other. Below his hands, on each side, are the figures of Nar and Nari (man and woman). The strange thing is beardless Brahma is similar to the Indonesian 9th century AD Prambanan sculpture.

The old remains of the sculpture of Lord Ganesha with the Navgriha panel are plastered in the newly built ridge platform of the Shiva temple, possibly the part of Sun temple. The panel has Surya (Sun) holding two flowers, Som (Earth’s Moon), Mangal (Mars), Budh (Mercury), Brihaspati (Jupiter), Shukra (Venus), Shani (Saturn) and Rahu (Uranus) - Ketu (Neptune) sculpted together as the part of Lalatbimb (doorway of the temple), Sun God with other eight planet deities standing together shows dynasty’s knowledge of Solar System far earlier before 7th century AD (figure 9).

The sculpture of Malyudh is plastered in the Shiva temple. It shows wrestler’s fighting, with them sculpted musicians and two people are shown holding flags (figure 10).

Figure 9: Old Nav Griha Sculpture

Figure 10: Malyudh

A colossal image of Lord Ganesha is kept in the Shiva Temple of Vasantgarh; the image belongs to the time of Maharana Kumbha. The Idol is Chaturbhuj Ganesha, shown holding Parshu (axe) in his upper left hand, Laddoo (sweet balls) in his lower left hand, rosary in his upper right hand and Pasha in his lower right hand. The posture of the idol can be identified as sitting in the Lalit Aasan, with a serpent encircling the belly, Mushak (mouse; considered to be his vehicle) sitting near his foot and the two wives- Riddhi and Siddhi- on either side. An identical sculpture was found in Zawar, Udaipur by our team.

The sculpture of the river-goddess (sacred river Ganga standing on Makra and sculpture of Yamuna standing on a turtle) is sculpted on the doorway of the temple, especially in early Gujara-Pratihara art. It is sculpted downward (left and right portion of a door).

In the back side of the Shiva temple at Vasantgarh, a headless idol of an unidentified Tirthankara was found. A beautifully sculpted Narsimha avatar, shown crushing the body of the demon named Hiranyakshayap, which may be a part of the panel of Dasavtar of Vishnu was also added to our findings. Both sculptures are made of pure white marble stone.

Rajputana was historically known for its inclination towards business having a greater significance given to the Vaishyas (traders’ class) and Jain folks who were in charge of the sale of goods and commerce over the community (Taknet, 2016, p. 30).

The geography of Rajasthan has made it possible through a network of internal and external trade routes throughout the state (Taknet, 2016, p. 30). Generally, in the early medieval period, the flourishment of many towns went hand in hand with the establishment of an administrative centre and fort, swelling up to include Qasba (boroughs) and trading areas amongst the many facets of growth, that were added by the various ruling dynasties to the already established settlements or the new ones (Hooja, 2006, p. 283).

This period flourished from around the 7th century AD to the 18th century AD (Talesara, Ancient Defence Structures or Forts in Sirohi District, 2022, p. Conclusion). In history, this period was marked by the growth of the silk route & other trade routes and the invasions from the Arabs or other hostile kingdoms. This is the reason why in this period, various dynasties started building stronghold fortifications around cities and built forts to protect the trading towns like- Nagda, Ahar, Chatsu, Arthuna, Chandravati-Abu, Chandrawati –Jhalarapatan, Lodrava, Bhinmal, Jalore (Jabalipur), Mandore (Mandavyapur), Sambhar (Shakambhari), Chittor (Chitrakut), Ajmer (Ajay-Meru), Jaisalmer, Sanchore, Nagaur (Ahichchhatrapura), Phalodi (Phalavardhika), Pali, Nadol, Sandera, Nadlai, Korta, Khed, Dholpur, Didwana, Bayana and Jaisalmer . (Hooja, 2006, p. 283).

Primarily, literary and epigraphical sources show that other than metal and limestone sculptures, the trade items that passed through Rajasthan were - wheat, the Moong lentil and other lentils (pulses), resin, oil, betel leaves, spices, salt, Manjistha (red madder), horses, textiles, coral, camphor, musk, sandalwood, the Agar incense, nutmeg, coconut, sugar and Jaggery (molasses), pepper, ivory, by-products of the Mahua (B. Latifolia) tree and dates. (Hooja, 2006, p. 283).

Goods originating from other regions frequently made their way to Rajasthan’s markets, or were sent via trade routes in the area in order to reach marketplaces that were more advantageous (Hooja, 2006, p. 283).

The ancient Mount Abu has been described as ‘Ashtadshashata Mandala’ which tells us that the Arbuda kingdom contains Ashtadshashata Mandala, meaning 1800 villages (Jain K. , 1972, p. 34). That explains its spread in a larger territory. If we look at the city of Palanpur, which today lies in the Gujarat region, was a prosperous city founded by the Parmar king, Prahaldan Dev in the thirteenth century, which connects it with this spread. (Rajyagor, 1979, p. 726). This city was well known for the perfume and diamond industry (Rajyagor, 1979, p. 726). Still, the Palanpur area is famous for these industries. In the medieval period, trading cities like Chandrawati, Nurhad, Bhinmal, Osiyan, Bhilwara, Nagaur, Pali, Malpura, Churu and Shergarh were noticeable trade cities and were connected with many trade routes (Taknet, 2016, p. 30).

In the Mauryan period (Circa 322 B.C.185 B.C.), Gujarat documented a significant period according to the epigraphic sources that testify Mauryan emperor Chandragupta and his grandson Ashoka ruled over Gujarat (Shah, 1959, p. 79). As per the Jain tradition, Mauryan king Samprati (grandson of Ashoka) ruled over Saurashtra, an important ancient port town in Gujarat (Shah, Akota Bronze, 1959, pp. 79, 80). Though there is direct evidence that claims Gujarat is a Mauryan province, there is no doubt that it was an ancient highway between the adjoining provinces of Rajasthan and Deccan under the Mauryan rule (Shah, Akota Bronze, 1959, p. 80).

The site of the ancient city of Ankottaka (modern Akota), which seemed to be an important trading centre of Vallabhipur situated to the west of Baroda was discovered early in 1949 by M.D. Desai (Shah, Akota Bronze, 1959, p. 80). The city flourished with nucleated habitation on the right bank of the river Vishwamitri (Rajyagor, 1979, p. 826). The site used to be located near Ankota(Banyan) trees, that’s why in contemporary times, the city was known by the name Ankottaka (Rajyagor, 1979, p. 826). The bronze handle of roman Amphora pottery was discovered in Akota which tells about the commercial trade with Rome (Rajyagor, 1979, p. 81). During the popularity of Gujara-Pratihara culture, with Bhillamala as the possible centre has to its credit the creation of a Western School of Indian sculpture in the 7th century AD; Sarangadhara was the pioneer of this artistic movement, an event referred to and written by Buddhist Tibetan monk Taranath (1575-1634) in A.D. 1608. (Shah, Akota Bronze, 1959, p. 25). The ancient Ankottaka suburb, as already mentioned is situated near the banyan trees which is called Vadapadraka (which means village amidst banyan trees), giving the name Vadapadraka/Vadodara to Baroda in ancient times whereas the name Baroda was given by English travellers (Rajyagor, 1979, p. 826). According to the traditional records, the Ankottaka suburb was in existence from at least the 5th century AD (Rajyagor, 1979, p. 826) and a king before the 9th century AD gave the suburb of Ankottaka as a donation to Chaturvedi Brahmanas (Rajyagor, 1979, p. 826).

The bronze and brass of the Vasantgarh hoard were first mentioned as the actual existence of the Western School referred to by Taranatha but have not been discussed eruditely, though some of the images are illustrated and referred to as the bronze hoard of Ankota. No doubt, running of extensive trade, especially during the Solanki period and later in the 14th to 17th centuries, a large-scale number of sculptures were manufactured at Dungarpur (the southernmost part of Rajasthan) and other places. Some of the sculptures were colossal and heavy weighted, notably the Chaumuka sculptures at Achalesvara of Mt. Abu (Shah, Akota Bronze, 1959, p. 25). One Jain sculpture in Dilwara Jain Temple in Mt. Abu possibly was a product of Vasantgarh because its weight is around 5000 Kg which shines like gold and is brass sculpture containing zinc. In AD 1134, it was very difficult to transport such heavy sculptures at 1200 MSL in height. The trade of Zinc to Vasantgarh in 7th Century AD is justified through 16 state geologists meeting according to Samoli Inscription (Kumar, 2021).

It may be possible that a large number of metal sculptures were produced at different sites of Mt. Abu kingdom. These sites may have learnt bronze sculpting from the Vasantgarh School of Art which is a potential reason for having similar artistic beauty. The small-scale industries might also have played their role in the manufacturing of bricks, pottery making and possibly textile and products of semi-precious stones. These along with the other industries no doubt needed skilled labourers & workers controlled by the money lenders or capitalists who set up the trade & business in Sirohi. The transformation of the city into a well-fortified zone with consistent watch towers may be used as an indicator towards the prosperous trade and commerce of the region which needed to be patronized and protected from possible hostility from enemies. That development of temples and fort indicated collection of taxes by administration.

Unveiling the riches of Vasantgarh, it can now be concluded that the city existing before the seventh century AD had its heritage treasure bejewelled with creative arts, metal industry and blooming trade. The few ancient copper mines and large dumps of slag and raw material stand as excellent evidence, backing the term Vatakara. Analysing the metal art, the challenging aspects of using two or more metals in a single sculpture and the stone sculpting, it can be assertively said that the industrial development of Sirohi was extensive; smelting and metallurgical artistry required the use of skilled labour which were a feasible aspect for Vasantgarh. Our team's XRF test on a sculpture shows that most sculptures are likely brass hoards, not only bronze hoards as suggested by previous scholars and in comparison, to Akota Bronze. The trade and commerce of the region were obviously prosperous with the mass production by the art industry and other small-scale industries as well as various routes of trade connecting the zone with the major commercial centres. Sirohi trade was so rich that it was not only connected to western Gujarat but also it has business trade links with the silk-road.

However, the major challenge ahead of us is the continuous expansion of modern cement mining and factories, spreading rapidly towards the Vasantgarh Fort and the capturing of fort land for residential or commercial purposes. It is for the authorities and government to take the right action and prohibit the destruction of our invaluable past which if not stopped, will ravage the entire site in the coming 6 to 8 years.

Vijay Kumar, T. (1990). Sirohi rajaya ka Rajnaitik itihasa avam sanskritik itihasa. Jodhpur: Rajasthani Granthagarh & Hill Top Publisher.

Bhandarkar, D. (1907). Progress Report of Western Circle (1905 - 1906). Bombay: Government of Bombay.

Chandra, M. (Ed.). (1971). Prince of Wales Museum Bulletin No. 11. Bombay: Prince of Wales Museum of western India.

Chandra, M. (1977). Trade And Trade Routes In Ancient India. New Delhi: Abhinav Publication.

Hooja, R. (2006). A history of Rajasthan. New Delhi: Rupa. Co.

J.S. Kharakwal, A.K. Pokhariya & Et. al. (2016). Preliminary Observation of Excavation at Chandravati, Sirohi, Rajasthan. Shodh Patrika, 67(1-4), 20-54.

Jain, K. (1972). Ancient cities and Town of Rajasthan. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas.

Jain, M. (2019). Flight of Deities and Rebirth of Temples. New Delhi: Aryan Book International.

Keilhorn, F. (1981). Vasantgadh inscription of Purnapala the Vikrama Year 1099. (H. E, & K. Sten, Eds.) Epigraphia Indica, IX (1907-1908), 10-15.

Kumar, A. (2021). Archaeometallurgy of Rajasthan. Udaipur: Sahitya Sansthan, Jrn Rajasthan Vidyapeeth.

Malekandathil, P. (Ed.). (2016). The Indian Ocean in the making of Early Modern India. New Delhi.

Pande, G. (1984). Jain Thought and Culture. Jaipur: University of Rajasthan.

Rajyagor, S. (Ed.). (1979). Gazetteers of Vadodara District. Ahemdabad: Government of Gujarat.

Saini, R., Talesara, P., & Bahuguna, A. (2022). The Archaeometallurgy of Vasantgarh, Sirohi, Rajasthan. London Journal Press, 22(10), 27-35. doi:10.5281/zenodo.7497583

Shah, U. (1956). A Bronze hoard from Vasantgarh. Lalit Kala : A journal of oriental Art, Chiefly Indian 1-2 (1955-56), 55-65.

Shah, U. (1959). Akota Bronze. Bombay: Bombay: Department of Archaeology.

Taknet, D. (2016). The Marwari Heritage. Jaipur: IntegralDMS.

Talesara, P. (2022). Ancient Defence Structures or Forts in Sirohi District (Vol. http://hdl.handle.net/10603/410620). Pindwara: Madhav University. doi:10.5281/zenodo.7396196

Talesara, P., & Bahuguna, A. (2020a). Archaeological Exploration of Sirohi District, Rajasthan. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 25(2), 14-19. doi:10.9790/0837-2502041419

Talesara, P., & Bahuguna, A. (2020b). Decoding of the Story Superimposed of Buddhist Sculpture unearth from Bharja and testifying its relation to this Silk- route area of Sirohi District, India. Technium Social Sciences Journal A new decade for Social changes, 7(A new decade for social changes), 302-311. doi:10.47577/tssj.v7i1.410

Talesara, P., Bahuguna, A., & Thakar, C. (2021). Archaeology of Bandiyagarh, Sirohi, Rajasthan, India. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 8(1), 1-21. doi:10.1080/23311983.2020.1870808

Talesara, P., Bahuguna, A., & Thakar, C. (April 2020). Archaeological Exploration of Defence Structures & Fortress City based on Ancient Folklore of Mount Abu, Rajasthan, India. International Journal of Management and Humanities, 99-103. doi:10.35940/ijmh.H0832.044820

Talesara, P., Bahuguna, A., Mani, B., Khan, A., & Thakar, C. (2021). Architectural Evolution of Defence Structures due to High Seismic Activity: A focus on Ancient Silk-route Cities of Sirohi District, Rajasthan, India. Rajasthan History Congress, 115-137. doi:10.5281/zenodo.7395951

Talesara, P., Khan, A., & Thakar, C. (2020). An archaeological documentation and investigation on fortification discovered in the Aravalli range, Rajasthan. (B. Bhadani, Ed.) Rajasthan Archaeology & epigraphy congress, 1(feb), 280-294.