Department of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Nigeria, Nsukka

DOI: 10.55559/sjahss.v2i03.92 | Received: 07.03.2023 | Accepted: 16.03.2023 | Published: 25.03.2023

ABSTRACT

Despite the embodied presence of self-taught art in Nigeria’s contemporary art space, the contributions made by self-taught artists in advancing the modernist landscape of contemporary art in Nigeria have remained largely understudied. Employing historiography and stylistic analyses, this article examines the modernist affirmations in the art of Segun Aiyesan, a self-taught Nigerian artist. It traces his artistic development as well as the various factors that influenced and shaped the modernist sensibilities evident in his art. Situating the discourse within the idiosyncrasies of Nigerian and Western art traditions, the study highlights how Aiyesan’s eclectic and experimental approach to art, in conjunction with his effectual application of artistic talent and imagination, enabled him to transact his own brand of modernism, and how its stylistic and aesthetic registers offer a deeper understanding of the multifarious landscape of modern Nigerian art. Key attributes that frame Aiyesan’s art practice include the use of unconventional painting formats, multiple engagements of a particular subject matter using diverse compositional frameworks, and the continuous re-appraisal and re-invention of formal language. Thus, his art is very dynamic, expressive and constantly evolving.

Keywords: art modernism, modern Nigerian art, Segun Aiyesan, self-taught art, self-taught artists

|

Electronic reference (Cite this article): ODOH, G. (2023). Transacting the Modern in the Works of Segun Aiyesan, a Self-Taught Nigerian Artist. Sprin Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, 2(03), 12–28. https://doi.org/10.55559/sjahss.v2i03.92 Copyright Notice: © 2023 Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license. |

1.0 Introduction

The art ecology in Nigeria comprises diverse agents and agencies whose contributions have made contemporary Nigerian art a critical factor in the global art space. Formally and informally trained artists are critical players in this creative environment. Regrettably, despite the manifest presence and contributions made by self-taught artists in advancing the modernist sensibilities of Nigerian art, self-taught art has not gained currency as an important field of study in art historical studies in Nigeria. In Western art cultures, the term "self-taught artists" is believed to carry a lot of connotations and interpretations because of the confusion caused by the various descriptive terms for self-taught art (Janis, 1999). Some of these descriptive labels include Art Brut or Outsider Art, Folk Art, Non-Professionals, Sunday Painters, Popular Painters, Primitives, and Naive-Primitives. These categories of self-taught art mirror the actors, agencies, and conditions that gave rise to respective artistic peculiarities. Although such terminologies appear to be non-existent in historical narratives on modern Nigerian art, they offer useful frameworks for interrogating the footprints of self-taught art operating either at the centre or margins of mainstream art in Nigeria.

The development of a critical space that engages the field of self-taught art within Nigeria’s contemporary art space is very important. This will expand the conceptual and contextual fields of modern art history in Nigeria and also promote the works of self-taught artists as constituting an important signpost that broadens understanding of the multi-stylistic landscape of modern art practice in Nigeria. The art of post-independence Nigerian artists (including self-taught artists whose art operates within the corridors of mainstream art) is usually influenced by two critical factors: Nigeria’s postcolonial art experiences and the artistic sensibilities of modern Western art. Thus, these two influential fields provide important markers for appraising the art practices and stylistic predilections of many post-independence artists in Nigeria (Bosah & Edozie, 2010; Castellote, 2012; Ofoedu-Okeke, 2012). They also allow for the tracing of creative influences, especially how some of the art traditions domiciled within these two artistic domains moderate the eclectic, experimental, and modernist attitudes noticeable in the art practices of many Nigerian artists.

Figure 1: The artist, Segun Aiyesan

Scholarly interest in the biographies and art practices of self-taught artists offers insightful contexts for understanding the nature and degree of involvement of self-taught artists in Nigeria’s contemporary art space. In a bid to expand discourse in this area, this article seeks to examine the modernist affirmations in the art of Segun Aiyesan (Figure 1), a self-taught Nigerian artist. The objectives of the study are anchored on the following lines of inquiry: How did Aiyesan’s interest in art develop? What are the factors that shaped his artistic sensibility? Considering the connectedness of his art to mainstream art practice, what has he borrowed from it and what has he given back in return? If modernism foregrounds new ways of engaging ideas and media through experimental vigour, how does the eclectic and experimental outlook of his art project this modernist ethos? The study employed biographical and stylistic analyses in seeking answers to these questions. The use of these two approaches draws from the belief that, although artists’ monographs invested in biographical and stylistic analyses are seen as amounting to basic research, which takes the pedestrian approach of using dates and times as markers for identifying causal links between an artist’s life and art, such an analytical approach is necessary in fashioning ways of engaging artists, especially to find out if their works align with their theoretical and critical positions (Ogbechie, 2015, p. 9).

2.0 Outlining the field

Several self-taught artists in Nigeria have made conscious efforts to situate their art practice at the centre of mainstream art (Odoh, 2014). The modernist sensibilities exhibited by these artists derive from their responses to multifarious factors that include their exposure to established art traditions and conventions, as well as the social, political, and cultural dynamics of a globalised environment. An important factor that underlies these encounters has to do with how self-taught artists (including formally trained artists) deploy artistic talent and imagination in mediating these experiences.

As far back as 1919, T. S. Eliot’s essay, "Tradition and the Individual Talent," explored the relationship between tradition and artistic talent and its role in the creative process. In his analysis of Eliot’s essay, Pateman (2005, as cited in Odoh, 2014, pp. 5–6) notes:

...On the one hand, there is the desire to be truly creative, to produce something new and not merely a novelty within well-worn and well-understood forms. On the other hand, there is a pressing need for genius to learn from genius. The tension produces perfectly researchable anxieties of influence...Some artists can happily enter into and work through an encounter with the art of their predecessors, acknowledging that they are learning and what they are learning from them. Others are anxious lest influence spoils their own individual talent, and they have to deny and repress such influence. Artists will often move more or less uneasily between these two relationships to what has already been created.

How artists work through this relationship plays a crucial role in the development of art styles and artistic sensibilities. The modernist affirmations in Segun Aiyesan's art reflect the processes and influences that he has appropriated in his search for that unique artistic voice that would effectively and expressively communicate his vision of the world around him. Perceivable influences of artistic sensibilities that could be traced to art modernism in Nigeria and in the West attest to the eclectic spirit that drives Segun Aiyesan’s studio practice. However, such an eclectic disposition raises questions about issues of identity and authenticity, especially when self-taught artists are involved.

In his essay, "Crafting Authenticity: The Validation of Identity in Self-Taught Art," Fine (2003, p. 155), makes the argument that "although the domain of self-taught art is ostensibly defined by the fact that the artists have not been formally trained, in practice, self-taught art is known through the social position of the creators." In his exploration of the idea of personal legitimacy as a critical component in the valuation of self-taught art and also as a means of conferring value on aesthetic authenticity controlled by an elitist cultural patrimony, he tries to situate the artists within a set of social positions that frame their identity within this art world, arguing that the social positions of these artists, and by extension, their identities, moderate their artistic productions and thus separate them from groupings based on similarities in form, content, or intention (Fine, 2003). However, applying this descriptive model to Aiyesan’s art is problematic. This is so because his social position is not markedly different from that of his counterparts who are formally trained. Again, having situated his art at the centre of mainstream art, where he has built quite a reputation as an accomplished artist, his art, along with that of formally trained artists, is subjected to the same politics of representation and economics of the marketplace that drive mainstream art. Consequently, rather than focusing on his social position as the key marker of his identity and authenticity, emphasis should be placed on the experiences that shaped his artistic sensibility and positionality within the dynamic landscape of contemporary art. Thus, in order to meaningfully engage and understand how Nigeria’s art modernism intervened in Segun Aiyesan’s art, it is necessary to briefly illuminate important artistic experiences that shaped the modernist outlook of the 20th and 21st century visual art practice in Nigeria.

The naturalistic art produced by Aina Onabolu, a self-taught artist, during the colonial period in the first decade of the 20th century represents the earliest manifestation of self-taught art and art representation after Western ideals within a modernist framework (Okeke-Agulu, 2015). The novelty of Onabolu’s achievement derives from his having countered the prejudicial position of the colonialists that Africans are incapable of artistic representation after Western models. As Okeke-Agulu (2015) notes, Onabolu "developed a visual language that was new, ideologically progressive, and... avantgarde". For a greater part of the intervening years before Nigeria’s independence in 1960, the art of naturalistic representation as espoused by Onabolu was very much celebrated and functioned as a nationalist tool against colonialism. Within this period, the teachings of K. C. Murray, an expatriate art teacher who arrived in Nigeria in 1927 to assist Onabolu in the teaching of art in Nigeria, placed emphasis on the incorporation of African indigenous cultural sensibilities into art making, an ideological position that was at odds with that of Onabolu (Okeke-Agulu, 2015). By the time Nigeria’s art modernism transited into its postcolonial variant after the country’s independence in 1960, the influence of Onabolu’s and Murray’s approaches to art pedagogy, as well as the activities of cultural actors and agents like Ulli Beier, Ben Enwonwu, and the Zaria Art Society, provided distinct ideological and artistic subjectivities that shaped the nature, form, and trajectory of postcolonial modernism in Nigeria.

The melding of indigenous African cultural sensibilities and Western representational attitudes was pivotal to the development of art modernism in postcolonial Nigeria. This idea formed the foundation of the natural synthesis ideology put forward by the members of the Zaria Art Society, an art commune formed by students of the Nigeria College of Arts, Science, and Technology (NCAST), Zaria, in 1958. Guided by this ideology, concerted efforts were made by the student-artists to produce works that articulated artistic modernism in Nigeria’s post-independence art space (Okeke-Agulu, 2015). The concept of natural synthesis also enabled the Nigerian artist to engage "with his ancestral heritage, with Europe, and with the postcolonial world" on his own terms (Okeke-Agulu, 2015, p. 88).

Beyond the walls of NCAST, some members of the Zaria Art Society like Uche Okeke, Yusuf Grillo, Bruce Onobrakpeya, and Demas Nwoko, through personal reading and application of the natural synthesis ideology in their respective studio practices, expanded the modernist landscape of 20th-century Nigerian art (Okeke-Agulu, 2015). Using the intellectual and artistic proceeds of their Zaria and post-Zaria experiments as a pedagogical tool, Yusuf Grillo and Uche Okeke, in particular, inserted their respective brands of modernism into the creative culture of the art departments at Yaba College of Technology (YABATECH), Lagos, and the University of Nigeria, Nsukka (UNN), where they respectively taught and held administrative positions. The proliferation of art training institutions further expanded the modernist landscape of post-independence art in Nigeria. This equally gave rise to the use of descriptive labels like Yaba School, Zaria School, Nsukka School, Benin School, Auchi School, and IMT School to allude to the creative identities of art training institutions based on the peculiarities of their ideological leanings and stylistic idiosyncrasies. The works of many artists who trained in these institutions are influenced by the dominant artistic codes that shape the culture of art pedagogy and art practice in these art institutions.

The multi-dimensional outlook of contemporary art practice in Nigeria gives an indication of the "complexity of its great history and the constant amalgamation of old and new forms" (Ofoedu-Okeke, 2012, p. 13). Its diversity and expansiveness create contradictions and ambiguities in terms of meaning, definition, and categorisation (Ofoedu-Okeke, 2012). Various interpretive frameworks have been used to interrogate its polyvalent structure. Some of these frameworks use epochal events and periods in Nigeria’s history to categorize Nigeria’s art modernism (Ofoedu-Okeke, 2012; Odita, 2010; Jegede, 2010; Ofoedu-Okeke, 2015). For instance, Ofoedu-Okeke (2015) locates Nigeria’s art modernism within the following periods: the pre-independence era (1950–1960); independence and post-independence eras (1960–1970); civil war, aftermath, and the oil boom (1970–1980); the structural adjustment Programme era (1980–1990); and regeneration and the new century (1990–2010). What these categorisations suggest, with respect to the artists who are listed within each epochal period, is that they represent when these artists were most active as well as the prevalent socio-political experiences that conditioned their art at that point in time. However, such classifications do not necessarily frame Nigerian artists within fixed, inflexible boundaries, as their art practice sometimes straddles two or more periods.

The categorisations put forward by Jegede (2010) and Odita (2010) are quite instructive. Although his interpretations were based on his analysis of works in some private collections in Lagos, Jegede says this of the artists:

There are those who belong in a representational school. I use this term with all the elasticity that it conjures. Within this subsides a figurative camp that can also be broken into sub-categories from the expressive to the mimetic. A great number of contemporary artists in this collection belong within this division. It is arguable that since the days of Aina Onabolu and Akinola Lasekan, this has remained the dominant genre, save some stylistic updates and differentiation. (Jegede, 2010, 51)

He also sheds light on another group of artists:

The second camp harbours a remarkable stylistic thrust and a break from the popular genre. What characterises artists within this category is a flatness of surface and a deliberate disregard for perspective and depth of field, which are standard design repertoire of abstract expressionism. The usual recourse to illusory three-dimensionality is dispensed with. (51)

Along the curve of their artistic developments, a good number of Nigerian artists navigate between these two stylistic zones as they search for that artistic voice that adequately suits their respective creative temperaments and also expressively communicates their ideological and critical positions. As will be highlighted later, Segun Aiyesan's art is emblematic of Nigerian artists whose art style cuts across these two stylistic zones. Based on other considerations that are directly connected to existential conditions in Nigeria, the country’s artistic expression is characterized by four major styles: environmental art, convergent art, traditionalist art, and synthesised art (Odita, 2010, p. 2). Odita also acknowledges the influence of globalization on Nigeria’s art landscape. He is of the view that to better understand the "multiple, shifting, and constantly expanding nature of today’s Nigerian artistic expression, it is important to consider the nature of this force-acculturation that impacted and still impacts contemporary art and artists in Nigeria" (Odita, 2010, p. 1).

Unarguably, the impact of globalization on the contemporary art space has opened up new contexts of meaning, history, and art trends. Ogbechie (2015) notes that globalism as a theoretical framework in art historical analysis interrogates issues of mobility, circulation, networks, and connectivity in building historical narratives across transcultural spaces. His broad view of the global contemporary age is seen as deriving from the aggregate function of diverse postcolonial experiments, which construct modernisms that are region-specific and thus negate "earlier models of historical analysis that focused mainly on supposedly autonomous national or cultural developments rooted in defined and separate spaces (Ogbechie, 2015, p. 6). The views expressed above, in some sense, make allusion to certain factors that shape art practice in the global contemporary age. Some of these factors echo the politics of identity, inclusion, exclusion, and representation engendered by Western hegemonic viewpoints, which have been criticized for relegating African art and artists to the margins (Oguibe, 2004). However, globalization has played a key role in breaking down creative borders and facilitating the assimilation into mainstream art narratives of works by many African artists who had hitherto operated at the margins. Similarly, Enwezor, Okeke-Agulu, and Costanza (1980, p. 4) note, "African artists have been beneficiaries of the globalising phenomenon that has included the rise of biennials and art fairs and the unprecedented surge in collecting art on a world-wide scale." Many Nigerian artists, including Segun Aiyesan, have benefitted from the globalising agencies outlined above. Segun Aiyesan’s participation in the 2009 Florence Biennale further reinforces this. He described the experience as very informative and aesthetically rewarding. (Personal communication, September 14, 2013)

Based on the discussions carried out so far, it is quite obvious that contemporary art in Nigeria operates in a constantly evolving space shaped by existential conditions and experiences. It is contingent on artists who intend to successfully navigate this complex and challenging terrain to have a relatively firm grasp of the dynamics that shape life and art within this dynamic environment. In the following section, I situate Segun Aiyesan’s art within these creative environments and their associated histories in order to understand how his works transact and also advance its modernist sensibilities.

3.0 Modernist Affirmations in Segun Aiyesan’s art

In 2019, Dymentiona, a solo exhibition by Segun Aiyesan, opened for public viewing at Thoughts Pyramid Art Centre, Lagos. Although the exhibition reflected Aiyesan’s attempts to memorialize traumatic childhood experiences as well as to explore the complex landscape of human consciousness and imagination, the stylistic registers that carry both the formal and aesthetic accents of his visual language underscore his unrelenting artistic exertions on the altars of eclecticism and experimentation. The works shown in Dymentiona strongly highlight the conceptual and technical threads that anchor his creative vision and artistic sensibility. They also embody a constellation of real and imagined universes whose formal constructions shine light on the depth of the artist's imagination and the range of compositional tools employed in communicating the labyrinthine landscape of human psychology and experience.

The eclectic and experimental outlook of Segun Aiyesan’s studio practice underlines his willingness and open-mindedness to engage diverse sources of influence and experience. He has drawn inspiration from various art traditions and art conventions, as well as from artists whose approach to art aligns with his own artistic subjectivities. In addition to the eclectic and experimental spirit that drives his studio practice, Aiyesan’s passion for art is equally instrumental to the evolving nature of his art. According to him,

…art has always been a part of my being, and life without it is short of a mediocre existence…I do not attempt to guide my source of inspiration or try to define it, because I have realized it’s a futile exercise, so I am alert to any situation I find myself, for any artistic extract I can harvest (Aiyesan, 2010, n.p).

Segun Aiyesan’s openness to creative influences and the creative resolve he has applied to mining the artistic possibilities inherent in such encounters are instrumental to the expansive nature of his studio output, stylistically and compositionally. His experimental attitude, mastery of colour language, and proficiency in the use of diverse painting media such as oil, pastel, watercolour, and acrylics also contribute to the vibrancy of his art practice.

Aiyesan’s artistic development followed a non-formal route. The passion he had for fine art provided the stimulus to explore its variegated landscape and limitless artistic possibilities. As a self-taught artist liberated from the regimented structures of formal art training institutions, he has shown unrestricted freedom in exploring the vast terrain of art and creativity. Segun Aiyesan was born on March 18, 1971, in the ancient city of Benin, where his father, who was in the military, was stationed at the time. He knew little of Benin, as his early childhood was spent in the cities of Ibadan and Lagos. He had his primary school education at Omolewa Nursery and Primary School, Yemetu, Ibadan. Comic books inspired his early interest in art, especially in the field of drawing. His fascination and attraction to comic books continued to sustain this interest in drawing well beyond his primary education. Segun Aiyesan’s secondary school education was at Ojo High School, Lagos, where his interest in drawing was further bolstered when, in his second year, he met two students, Rotimi Roland and Gbenga Adeyemo, who both shared a similar interest in drawing comics (personal communication, September 14, 2013). During this period, Aiyesan’s drawing skills improved considerably because of the healthy rivalry that existed between them. He developed an appreciable understanding of proportion and foreshortening and showed good compositional awareness.

After the completion of his secondary education, Segun Aiyesan gained admission to study electronics engineering at the Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Though his disposition towards analytical reasoning allowed him to settle comfortably in this field of study, his love for art continued to feed his passion for drawing. He made frequent visits to the Fine Arts Department of the University and made friends with many art students, some of whom actually thought he was one of them. The art department’s library was also not spared from his numerous visits. Through his interactions with student artists as well as information sourced from art-related literature, Aiyesan gained useful insight into the world of art. The works of the old masters and the creative ideologies of some Western art movements fascinated him. In an interview, he narrated that in one of the books he read, the 19th-century realist painter Jean Baptiste Corot was of the view that for one to become a great artist, one should do nothing but art. He also said that Corot’s statement haunted him then because he was fascinated with art but, at the same time, never wanted to practice art professionally (personal communication, September 14, 2013). Most of the drawings he produced during his undergraduate years at the university were mostly done in a naturalistic style.

Segun Aiyesan graduated from the university with a degree in electronic engineering in 1995. After graduation, he was posted to Port Harcourt for the mandatory National Youth Service Corps Programme and served with Chevron Nigeria Limited, an oil exploration company. He spent most of his time on an offshore platform, and as such, his options for recreational activities were very limited. He instinctively fell back to drawing. The drawings produced during this period, which were largely inspired by the environment, caught the attention of one of his friends, who requested a portrait painting of his sister, who recently got married. Despite Aiyesan’s insistence that he was not a professional artist, his friend was convinced of his ability to undertake the task based on the drawings he had seen. After completing the painting commission, he used the leftover art materials to paint in his free time on the offshore platform. The paintings he produced attracted the attention of expatriate workers who were willing to pay for them. This signaled a frenzied interest in his art. According to Aiyesan,

Even the helicopter pilot that used to take us to the platform commissioned me to do a lot of things. Then my superintendent at the office also found out that I could do some great paintings, and he also commissioned work for me. After the service year, I had so many people coming to me to make paintings. (Ukot, 2013 as cited in Odoh, 2014, p. 410)

These painting activities significantly contributed to Segun Aiyesan’s artistic development, especially during the intervening years before he made up his mind to become a professional studio artist. He also highlighted other art-related experiences that framed his pre-professional years:

I started hanging out with professional artists, exhibiting with them. At this point, I felt that this wasn’t what I wanted because the impression I had of artists was that they were always broke, but I just couldn’t stop. I kept getting drawn into it, and then one day, I did an exhibition, and then a guy came by and saw it, and he was really impressed. He said that he would like to hook me up with someone who would be able to help me showcase my work properly. He hooked me up with a white lady whose husband was working at Total. She started displaying my works at the exhibitions organized by Total (personal communication, September 14, 2013).

Segun Aiyesan’s art career as a full-time studio artist began in 1998, three years after he graduated from university. Lequesne’s (2004, p. 45) comments on the circumstances surrounding the early stages of Aiyesan’s art career are quite revealing. He stated that Aiyesan, then, never believed "that being an artist could be a profession as well as an adventure. Torn between two worlds, between two lives, it took him all of three years to stop struggling against the unavoidable and give in." At the early stages of his professional art career, Aiyesan's status as an artist with an engineering background drew quite a number of questions. At first, he always answered that he studied engineering but opted for a career in art. Later, he felt that this did not present a true picture of his status. He states:

I studied art far more than I studied engineering. I probably didn’t study it in an institutionalized manner, but I studied art because I studied a lot of works of art by old masters and current artists, and I bought a lot of books. In my younger days, I subscribed to magazines abroad. Every month, I used to stock up on art magazines... I have technical books which I have read over the years. It's not formal, but it’s a study. It is more of research. I do research a lot. I experiment. I try materials. A lot of my works are results of experimentation. (Personal communication, September 14, 2013)

Aiyesan’s explanation outlines a learning process and conceptual approach that are flexible and non-restrictive to a single or set of assumptions. It also foregrounds an eclectic attitude and a desire to engage with the unknown and the unconventional through experimentation. He describes his creative temperament as follows:

When I am thinking in a certain manner for a while, I get bored and I don’t get excited anymore, so I do lots of internal creation and I try to come up with new ways of expressing myself all the time. The search is what drives me. I don’t know what I am searching for, but I know I can’t be caught standing in one place (Aiyesan, 2010, n.p).

Segun Aiyesan’s eclectic and experimental approach to art is strongly reflected in the multifarious pictorial languages and aesthetic frameworks he has developed over the years. Like most experimental artists who want their works to be different, unusual, and unfamiliar to the point of looking peculiar and perplexing, the compositional strategies employed by the artist constitute what Jameson calls a "dominant variable" and refers to "that artistic element that the artist values over all others" (Jameson, 2010 as cited in Odoh, 2014, p.). Aiyesan’s experimentation with different compositional structures allows him to periodically re-appraise the trajectory of his artistic vision as well as the creative accent of his pictorial language. This attitude infuses both dynamism and a certain degree of unpredictability into his art practice. In re-echoing this, Olaku (2010) asserts,

it is difficult to predict the future disposition of his works because my instincts tell me that he is in a frenzied pursuit of ultimate satisfaction and fulfilment as an artist. My wise counsel is that you enjoy any ‘course’ he serves at any point in time.

In the course of Segun Aiyesan’s quest for artistic renewal, his footsteps have been directed towards the vast landscape of art history. He makes frequent stopovers at creative frontiers made popular by master artists like Leonardo Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Monet, Rothko, and Picasso, among others. To quench his artistic thirst, he drinks from the ideological springs that watered the aesthetic fields of the realists, impressionists, expressionists, fauvists, and cubist artists. The works of renowned Nigerian artists such as Kolade Oshinowo, Abiodun Olaku, Sam Ovraiti, and Gani Odutokun also enriched his journey of self-discovery (personal communication, September 14, 2013). The 19th-century realist painter Jean Baptiste Camille Corot had been mentioned earlier as having made a favourable impression on Segun Aiyesan during the early stages of his artistic development. Although Aiyesan did not strictly follow Corot’s methods, his approach to colour, form, and value, to a noticeable degree, conformed to the creative tenets put forward by Corot. However, in some of Segun Aiyesan’s paintings, the source of influence is all too obvious. For instance, his painting, Hope (Figure 2), shows the direct influence of Michelangelo’s painting, The Creation of Adam, although in Aiyesan’s work, Adam is re-imagined as a highly textured hollow sculpture-like figure with broken and dismembered body parts.

Figure 2: Hope, 2010, mixed media. Source: Segun Aiyesan

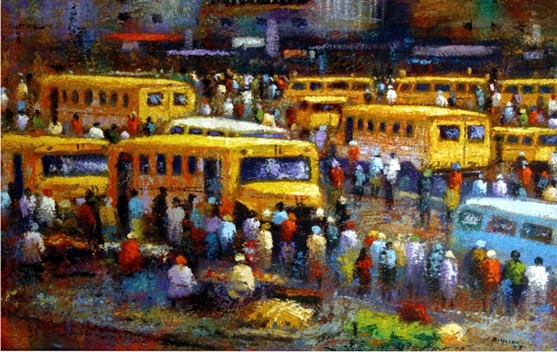

Segun Aiyesan's art style is anchored on three key elements: technical proficiency, expressive colour language, and multiple engagements of subject matter using different compositional strategies. His earlier works, particularly those produced between 1998 and 2001, were mostly executed in watercolour and pastel. These works reveal his early efforts at mastering the behavioural characteristics of these two media. As his studio practice evolved, he moved away from watercolour, focusing more on pastel and acrylic paint. Two paintings, Market Scene (Figure 3) and Lagos Cityscape (Figure 4), which he executed in the impressionist style, show his mastery of the pastel medium. It is important to point out here the strong influence of the stylistic sensibilities of the Yaba Art School on Lagos Cityscape. The Yaba Art School is reputed for pictorial realism and is also known for producing works that capture the ever-busy metropolitan city of Lagos and the ubiquitous presence of the iconic molue buses.

Aiyesan repeatedly engaged this subject matter between 1999 and 2003 using the pastel medium. The use of texture as a pictorial tool emerged in his art during this period, particularly in his experiments with pastel medium on roughly textured canvas supports. Also, his exploration of the impressionist art style gave rise to two sub-styles—the gestural and the slightly detailed. In the former, he employs a minimalist approach in the treatment of pictorial elements. The paintings executed in this style are rendered on highly textured surfaces, which encourage a bold and loose approach and pay less attention to detailing. Sharp edges and boundaries between colour planes are almost nonexistent. Forms flow into one another within colour fields that pulsate with energy and movement. The slightly detailed approach shows the depth of Aiyesan’s compositional awareness and approach to surface handling. In terms of pictorial aliveness, the artist’s proficiency in the pastel medium is clearly evident. His colours are fresh and cloaked in a rich, luminous ambience.

Figure 3: Market Scene, 2004, pastel, 36 x 40 inches. Source: Segun Aiyesan

Figure 4: Lagos Cityscape, 2003, pastel, dimension unknown. Source: Segun Aiyesan

Given the culture of experimentation that frames Segun Aiyesan’s studio practice, the tone of his plastic voice can shift quickly to acquire new compositional dialects. His pictorial language oscillates between the representational and the conceptual, allowing him to explore the varied formal and aesthetic fields embodied in these two representational modes. Colour plays an important role in these explorations and shows his understanding of its physical and psychological properties as well as its functionality as a carrier of emotional and aesthetic experience. Aiyesan has explored the colour devices favoured by fauvists, impressionists, and expressionist artists. His colour palette, at some point, referenced that of the Fauvist artists who, according to Kleiner (2009, p. 911), "liberated colour from its descriptive function and used it for both expressive and structural ends." Never Far Away (Figure 5) by Segun Aiyesan exemplifies the artist's vigorous exploration of the conceptual fields of painting and the dynamic role that colour plays in enabling its aesthetics.

Figure 5: Never Far Away, 2004, mixed media, 48 x 48 inches. Source: Segun Aiyesan

Pictorially, Never Far Away embodies the artistic sensibility of the post-modern era's Abstract Expressionism style. Its structural determinants situate it within the domain of both the chromatic and gestural abstractionist styles. The formalism mirrors the process employed by Hans Hoffman, the American abstract expressionist painter, which makes his paintings "a record of the artist’s intense experience of paint and of colour, of the process of painting, arbitrary, accidental, unthinking, automatic, direct" (De la Croix & Tansey, 1980, p. 857). The dominant image in Never Far Away is the head of a young woman submerged in a sea of energetic colour fields. Her facial features are treated in a loose manner. The countenance on her face speaks of loneliness and longing. Going by the title, the person or object to which these emotions are directed seems not to be far away and probably exists in the realm of shared memories. Other discernible elements in the work include flowers, a galloping horse, and a lizard, all rendered in a schematized manner and arranged horizontally across the lower region of the picture format. The artist may have used these elements to symbolically represent shared memories. The artist’s palette is predominated by red, yellow, green, and blue hues. The use of light tones in the treatment of the figure’s head contrasts with the surrounding background colours and makes it the focal point in the composition. The expressive use of colour in this painting is unmistakable.

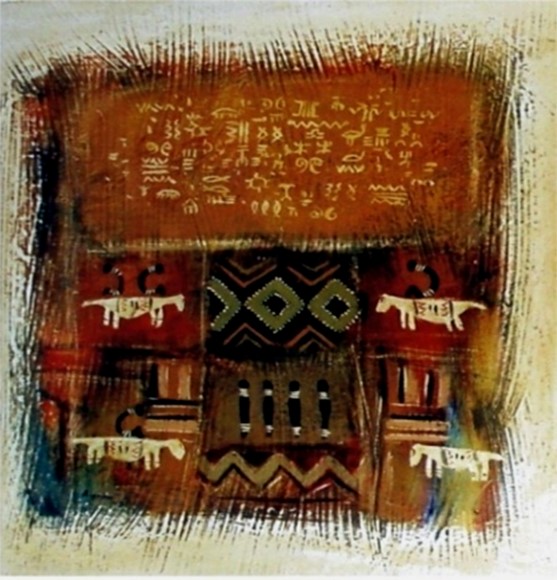

Segun Aiyesan’s eclectic borrowing from known art traditions is very evident in the KeteketeSeries (see Figures 6 and 7) and also in the painting Modern Woman (Figure 8). The works that belong to the Ketekete Series employ formal elements that are traceable to traditional African art. For instance, the painted equestrian figures in the Ketekete Series are rendered in a manner reminiscent of equestrian figures found in traditional African sculpture traditions. Also, some of the motifs and designs employed in the paintings echo indigenous design systems like uli and nsibidi. Compositionally, the Ketekete Series employs a design strategy whereby the pictorial surface is segmented using square and rectangular shapes of equal and sometimes unequal sizes. These geometric shapes become carriers of other pictorial elements, including motifs, symbols, animals, and human elements. In some instances, the arrangement of forms takes on a symmetrical arrangement, with the boundaries between adjacent forms either highlighted by outlining their edges with incised white lines or emphasised by tonal difference. Texture plays a key role in these compositions. Apart from the textured surface, the artist sometimes rips the edges of the canvas. This not only reinforces the tactile quality but also infuses a textile essence into the work.

Figure 6: Ketekete, 2001, acrylic, pigment powder and pastel,

dimension unknown. Source: SegunAiyesan

Figure 7: Ketekete, 2001, acrylic, pigment powder and pastel,

dimension unknown. Source: Segun Aiyesan

In Modern Woman, three likely sources of influence are identified in the handling of the figure. One, the treatment of the woman’s facial features echoes the approach used by Ernst Barlach in the work Head of the Güstrow Memorial, produced in 1927. Two, the treatment of the woman’s torso recalls the formalist tradition of analytic cubism. Three, the compact nature and fluidity of body forms make an allusion to the biomorphic sculptures of the Dadaist artist, Henry Moore. Additionally, there is a marked compositional deviation in Segun Aiyesan’s approach to surface handling. This is seen in the selective use of texture to create a tensional balance between active and non-active areas. His sculpture-like treatment of figures has become more forceful, infusing a three-dimensional quality into a two-dimensional surface. One could mistake Modern Woman for a photograph of a sculpture.

Figure 8: Modern Woman 2012, mixed media, 48 x 48 inches.

Source: SegunAiyesan

Multiple engagements with a particular subject matter are one of the defining attributes of Segun Aiyesan’s studio practice. Consequently, many of his works constitute parts of a series that includes the Omoge Series, Village Series, Market Series, Ying Yang Series, Men in Boxes Series, and Wait Series. Others are the Town Series, Ketekete Series, Smoking Series, Adam’s Blues Series, and Gele Series. Aiyesan has also experimented with unconventional painting supports. This engenders evocative compositional dialogues between the formalism of the works and the material properties of the painting support. He has experimented with trapezoidal formats, box-like formats, and amorphous formats. Works executed in a box-like format, such as Dawn of an Era (Figure 9), combine the three-dimensionality of sculpture with the plastic attributes of painting. The artist considers Dawn of an Era to be very special because it is the first work that anchored his three-dimensional explorations in painting. According to Aiyesan (2010, n.p.),

This work represents an awakening for me because it is the first of its kind. It defines a link between the conventional 2-dimensional planar platforms that I have explored over the years and a more robust 3-dimensional pictorial algorithm, having a sculptural leaning.

The box-like format used in Dawn of an Era has a depth of about four inches, which creates a relief impression when hung on the wall. In terms of its formal outlook, the work emphasizes a horizontal orientation and consists of four rectangular horizontal bands counterbalanced by the verticality of the cane with two coil-like formations positioned at its upper and lower regions. In the upper region of the picture format, the first and third horizontal segments, which appear recessed, are roughly textured with sand and rendered in light tones. The other two segments have a marble-like finish and are rendered in rustic tones of yellow ochre and reddish brown. Various inscriptions, rendered in white and incorporating ideograms found in the uli and nsibidi design systems, profusely decorate the second rectangular band. They create a dialogic space where meanings can be constructed based on one’s subjective reading of the painting’s thematic posture.

Figure 9: Dawn of an Era, 2009-2010, mixed media, 30 x 40 x 4 inches

© SegunAiyesan

Given the dynamic and expansive nature of Segun Aiyesan’s art practice, it is not uncommon to find stylistic traits that underscore the separateness and interconnectedness of his design strategies. This derives from his culture of constantly re-appraising the roles played by design elements in his art. At times, pictorial elements that played subordinate roles in a particular compositional framework are given dominant roles in other compositions. At other times, he arrives at new pictorial languages through the combination of two or more already existing compositional formats. Furthermore, he also develops new pictorial languages based on the results of his experiments with colour, technique, visual imagery, and the spatial engagement of formal elements. The evolution and trajectory of his art style can be effectively mapped and understood through the progressive reading of these formal pathways. Aiyesan’s involvement in mainstream art is not limited to the sphere of art production; he is also connected to the various agencies that shape the circulation, mobility, connectivity, and marketing of art through his participation in solo and group exhibitions, art auctions, and gallery representation. He also owns and operates InCollection Gallery, an art gallery located in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, where he presently lives and works.

4.0 Conclusion

Segun Aiyesan’s art practice highlights the critical footprints of self-taught artists in Nigeria’s contemporary art scene. His experimental and eclectic approach to art production has made for an art practice that is very dynamic, highly evocative, and aesthetically alluring. His interest in art started at an early age. Also, his passion for and commitment to art professionalism have enabled him to build a vibrant and successful art practice despite not having received formal training in art. His openness to diverse influences and his desire to seek new challenges at the frontiers of visual art practice are key factors that drive the eclectic and experimental outlook of his studio practice, as well as its modernist aspirations. His art is characterised by the use of unconventional painting formats, the multiple engagement of subject matter using diverse compositional frameworks, and the continual re-appraisal of formal language.

Segun Aiyesan’s studio practice is very dynamic and constantly evolving. Olaku (2010) notes that the artist’s "courageous, adventurous evolution in the creative realm has been marked by exciting, distinctive styles, despite his engineering orientation." He also points out that these styles and techniques have not been allowed to inhibit his natural skills and insight, but rather, they "have dramatically highlighted his strengths, such as poetic purposefulness in content and creative manipulation of media" (Olaku, 2010). Segun Aiyesan’s also sheds light on the relationship between his art and his personality:

I am a weird person. Sometimes I wonder if I am crazy. Sometimes when I paint, I talk to the art. I like loud music when I am working. It drowns out other sounds that would interfere with my thinking pattern. I wouldn’t consider myself an introvert, and I wouldn’t say I am an extrovert. So I guess I am somewhere in between. I probably have split personalities. In short, I think I have a couple of personalities. (Ukot, 2013 as cited in Odoh, 2014, p. 571)

Whatever it is that best describes Segun Aiyesan’s personality or personalities, his passion for art and his determination to explore its varied landscape are deeply embedded in its core. His art is humanistic and addresses contemporary experiences relating to the human condition.

Segun Aiyesan’s conceptual depth is matched by the expansiveness of his artistic imagination. These two qualities are important components of the creative loom with which he has woven different strands of existential experiences according to the dictates of his social and artistic visions. The transaction of the modern in his art, as Ugiomoh (2010) has identified in Nigeria’s art modernism, pays attention to the "sublime manifestation, always, of the new artistic form." Aiyesan understands that art is a journey leading to both familiar and unfamiliar places. It is also a journey that tests the limits of the human imagination. His contributions to advancing the stylistic and modernist fields of contemporary art practice show that his journey through the dynamic landscape of art has been eventful, exciting, and aesthetically rewarding. His art emblematises the embodied footprints of self-taught artists in modern Nigerian art and the critical interventions they have made in enriching its stylistic and aesthetic registers.

References:

Aiyesan, S. (2010). Artist’s Statement. In Epiphany (exhibition catalogue). Lagos: TND Press,

Bosah, C. & Edozie, G. (2010). 101 Nigerian artists. Ohio: Ben Bosah Books

Castellotte, J. (2012). Contemporary Nigerian art in Lagos private collections. Ibadan: Bookcraft

De la Croix, H. & Tansey, R. (1980). Art through the ages (7th edition). New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

Enwezor, O., Okeke-Agulu, C. & Costanza, E. (2009). Contemporary African art since 1980. Bologna: Damiani.

Fine, G. A. (2003). Crafting authenticity: The validation of identity in self-taught art. Theory and Society, 32(2), 153-180. https//www.jstor.org/stable/3108577

Jameson, A. D. (2010). What is experimental art? Available from http://bigother.com/2010/03/12/what-is-experimental-art/

Janis, S. (1999). They taught themselves. In A. Barr (ed), They taught themselves: American primitive painters of the 20th century (pp. 11-13). New York: Hudson River Press

Jegede, D. (2012). Art, currency and contemporaneity in Nigeria. In J. Castellotte, Contemporary Nigerian art in Lagos private collections (pp.39-52). Ibadan: Bookcraft

Kleiner, F. (2009). Gardner’s art through the ages (13th Edition), Boston: Thomson Wadsworth.

Lequesne, P. (2004). Introduction. In Nigeria: 48 hours with the children of the tortle (exhibition catalogue). Paris: Galerie M

Lewis, P. (2007). Tradition and the individual talent. Retrieved from http://modernism.research.yale.edu/wiki/index.php/Tradition_and_the_Individual_Talent

Odita, O. (2010). Understanding contemporary Nigerian art. In C. Bosah & G. Edozie (eds). 101 Nigerian artists (pp.1-10). Ohio: Ben Bosah Books

Odoh, G. (2014). Talent, eclecticism and experimentalism: A study of three self-taught Nigerian artists. (Doctoral dissertation), Department of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Nigeria, Nsukka].

Ofoedu-Okeke, O. (2012). Artists of Nigeria. Milan: 5 Continents Editions.

Oguibe, O. (2004). The culture game. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press

Okeke-Agulu, C. (2015). Postcolonial modernism: Art and decolonization in twentieth-century Nigeria. Durham: Duke University Press.

Olaku, A. (2010). Introduction. In Epiphany (exhibition catalogue). Lagos: TND Press.

Ugiomoh, F. (2010). Of modernism in contemporary Nigerian art. In C. Bosah & G. Edozie (eds). 101 Nigerian artists (pp.11-17). Ohio: Ben Bosah Books.