1, 2Department of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Nigeria, Nsukka

DOI: 10.55559/sjahss.v2i03.94 | Received: 08.03.2023 | Accepted: 17.03.2023 | Published: 26.03.2023

ABSTRACT

This article focuses on the diaspora work of Obiora Udechukwu, one of the Nsukka Art School's most well-known artists. When Udechukwu immigrated to the United States of America in 1997, he continued his pre-diaspora activities by teaching art at the university and working in his studio. The article uses historical and stylistic analyses to investigate how memory, nostalgia, remembrance, and culture-induced biases intervened in Udechukwu's diaspora work against the backdrop of the socio-political, cultural, and artistic experiences that frame his pre-diaspora art. The artist's diaspora works demonstrated that his pre-diaspora interests in Igbo culture, memories of the Nigerian civil war, and experiences of socio-political life in Nigeria have continued to influence the formal and thematic terrain of his work. His extensive use of text as a decorative and communicative tool, as well as the use of a design technique that merges two pictorial surfaces into one composition, are among the significant innovations that have taken place in his work. The study offers a developing interpretation of Obiora Udechukwu's artistic output. It also emphasizes how important memory, nostalgia, remembering, and prejudices brought on by culture are to diaspora art and to the (re)enactment of artistic identity by diasporic artists.

Keywords: Diaspora, Diaspora art, Nsukka Art School, Obiora Udechukwu, Uli art

|

Electronic reference (Cite this article): Odoh, N., & Odoh, G. (2023). Beyond the frontiers of the homeland: Obiora Udechukwu’s diaspora art, 1997-2010. Sprin Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, 2(03), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.55559/sjahss.v2i03.94 Copyright Notice: © 2023 Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license. |

1.0 Introduction

Obiora Udechukwu is a prominent artist of the Nsukka Art School, an art school known for a radical practice that uses ancestral knowledge to interrogate local and global spheres of practice (Ogbechie, 2009). His art strongly reflects the conceptual, intellectual, and experimental subjectivities that have enabled Nsukka artists to successfully navigate the corridors of mainstream art. Udechukwu’s embodied presence in the history of the post-Nigerian civil war art department of the University of Nigeria, where he taught for several decades, foregrounds the critical roles he played in the development and sustenance of an artistic identity that was dependent on the intellectual and creative exploration of the uli idiom. He was a part of the uli revivalist movement in the 1970s post-civil war Nsukka Art Department and vigorously championed the appropriation and use of uli art, an indigenous art of body and wall decorations essentially practiced by Igbo women of southeaster Nigeria, as a viable resource that could be synthesised into a modernist artistic language. Udechukwu is regarded as a major proponent of the uli idiom in the Nsukka Art School, and his art, in addition to reflecting other artistic idiosyncrasies, embodies uli’s formal attributes and aesthetics.

Several scholars have studied Udechukwu’s art (Ikwuemesi, 1992; Oloidi, 1993; Ottenberg, 1997; Ofoedu-Okeke, 2012; Wolf, 2014; Windmuller-Luna, 2014; Odoh, 2015; Okeke-Agulu, 2017). The artist has been described as representing the point of stabilization of the uli tradition, (Okpewho 1997, p. xii). Attention has been drawn to his contributions to the development of modern Nigerian art through his role as artist-poet (Agbai, 2003; Nwafor, 2005). In his analysis of Udechukwu's works, Aniakor (1987, p. 6) asserts that they "have a poetic and musical co-ordination in the lyricism of their lines, the subtlety and transparency of their execution, and in the skilful alignments of line-space boundary relations, anchored on the density of silhouetted micro-details." With respect to their compositional structure, he points out that "economy of means reaffirms the condensation of meaning" (Aniakor, 1987, p. 6).

The overt minimalist attribute of Udechukwu’s art, particularly his drawings, is directly linked to his skilful deployment of lyrical and rhythmic lines in creating dynamic compositions that thrive on what Ikwuemesi (1992, p.52) describes as "frugality and moderation." Simon Ottenberg’s book, New Traditions from Nigeria: Seven Artists of the Nsukka Group, published in 1997, provides very insightful essays on Udechukwu’s art. In addition to the rich biographical information on the artist, Ottenberg traces the various factors that influenced his artistic development and also shaped the stylistic contours of his art practice up to 1995. He reveals that what makes Udechukwu interesting as an artist is that he "keeps growing, moving in new directions yet retaining certain persistent traits: the diversity of his media, a wide range of subjects, and his use of uli and nsibidi" (Ottenberg, 1997, p. 153). In 1997, Obiora Udechukwu resigned from his teaching position at the University of Nigeria as a result of irreconcilable differences with the university administration. He migrated to the United States, and he took up a teaching appointment as Professor of Fine Arts at St. Lawrence University in New York. Similar to what he did while still in Nigeria, he taught art and also maintained a healthy studio practice. He retired from the university in 2018.

Unarguably, Udechukwu’s diasporic status presents a critical lens for appraising the stylistic trajectory of his art. As a field with expanding currency in cultural studies, Wofford (2016, p. 74) views diaspora as a "critical category for describing the effects of globalization on individuals and communities as they move around the world." If diaspora is characterized "by multiplicity, multiple practices, multiple world views," as Steve Nelson suggests (as cited in Wofford, 2016, p. 74), then diaspora art provides an instrumental handle for expressing this multi-dimensional outlook, especially as it relates to the negotiation of artistic subjectivities and identities and their affirmations and denials within contexts of real and imaginary homelands. In his description of the researchable anxieties that surround diaspora art, Farzin (2012, para 13) states, "The diaspora artist produces a kind of collective statement that is even more valuable if understood for what it is: artwork that emerges primarily out of the conflict of individual desires." These conflicting desires could emanate from the ambivalences created by the diasporic subject’s attempts to interpret and also communicate his or her condition of displacement through the filtering lenses of memory, nostalgia, remembrance, and ethnic or cultural identity.

Taking cognizance of the fact that Obiora Udechukwu spent a major part of his adult life in Nigeria and also given that his art primarily mirrors his experiences and memories of the Nigeria-Biafra civil war, his deep-seated interest in Igbo culture and worldview, and his critical responses to socio-political conditions in Nigeria, one is curious to find out if his diaspora experiences significantly reconditioned his creative sensibility and thus engendered perceptible formal, stylistic, and aesthetic shifts in his art practice. Employing biographical and stylistic analyses, this article focuses on Udechukwu’s diaspora art from 1997 to 2010. Against the backdrop of the stylistic landscape of his pre-diaspora art, the study seeks to examine the changes that may have occurred in his diaspora art. The study also attempts to find out the extent to which memory, remembrance, nostalgia, and cultural/ethnic identity—critical elements that have embodied presence in Udechukwu’s pre-diaspora art and which also play important roles in the diaspora experience—influenced his diaspora art. How these agentic factors functioned as creative sites in the (re)enactment of artistic identity and in the interlinking of the artist’s pre-diaspora and diaspora artistic subjectivities is also explored.

2.0 Framing Udechukwu’s pre-diaspora artistic experiences

To meaningfully appraise the stylistic and thematic landscape of Obiora Udechukwu’s diaspora art, reflections on his pre-diaspora art, which spans more than three decades, are very necessary so as to provide a basis for identifying stylistic and thematic shifts that may have occurred. However, given the numerous works of literature available on Udechukwu’s art, particularly Simon Ottenberg's seminal 1997 work, New Traditions from Nigeria: Seven Artists of the Nsukka Group, which provides extensive information on the artist’s pre-diaspora art practice, this study will be restricted to highlighting key aspects of his pre-diaspora art that provide comparative grounds for appraising his diaspora art.

Udechukwu’s art practice, while still resident in Nigeria, embodies diverse stylistic traits that foreground the influence of multifarious artistic, cultural, and sociopolitical experiences on his studio practice. His art is essentially two-dimensional and predominately composed of drawings, prints, and paintings. Odoh (2015) outlined key developmental phases that frame Udechukwu’s pre-diaspora art practice. These include his early artistic development (1964–1966), his wartime art (1967–1970), his re-appraisal of formal language through engagements with culture-based resources (1970–1979), the era of advanced linear oratory (1980–1991), and the era of profound colour exploration (1992–1995). These categorisations underpin the formal and thematic foundations of his art and offer insight into his varied responses to design challenges and his views on socio-political conditions in Nigeria. His experiences of the Nigeria-Biafra civil war and his memories of its traumatic experiences are recurring elements in his art.

As one of the major exponents of uli art in the Nsukka Art School, Udechukwu’s art is strongly influenced by the formal and aesthetic codes of the uli idiom, the Igbo traditional art of body and wall decorations that was appropriated and synthesised into a modernist artistic language in the post-Nigeria civil war art department of the University of Nigeria in the 1970s. The incorporation of the nsibidi design system into his art in the late 1970s, as well as his familiarity with the works of the Sudanese artist Ibrahim El Salahi and Chinese Li art, further influenced the lyrical and poetic tone of his pictorial language. With respect to the influence of Chinese painters’ poetic sensibilities on Udechukwu’s art, Windmuller-Luna (2014, p. 76) states:

By incorporating antiquarian elements of both Nigerian and Chinese culture to create his politically aware line drawings, Obiora Udechukwu created a new kind of contemporary African art. By directly and indirectly adopting modes of Song literati artistic creation, he enriched his understanding of Natural Synthesis, creating works of art that speak in global and local symbolisms, allowing for a multiplicity of meanings embedded within the lines of a single work.

The expansive nature of Obiora Udechukwu's art style encompasses diverse representational modes, including naturalism, conceptualism, stylization, and abstraction. His early works were quite naturalistic and addressed everyday life. Examples are Third Class Coach (1966) and the gouache painting, Nsukka Market (1966–67). His wartime art moved away from naturalism, employing stylization even to the point of distortion. Oloidi (1993) describes his style during this period as "subjectively representational." The works Exile Train (1968), Blue Figures (1968), and Uncontrollable Grief (1970) embody this stylistic outlook.

Subsequent works produced after the civil war reflected his search for a creative voice that expressively captured the artistic, social, political, and cultural experiences of post-civil war Nigerian society. Although the socio-political content of his art basically remained unchanged, its formal outlook was radically transformed by the artist’s intellectual and experimental engagements with the formal attributes and ethno-aesthetic of the nsibidi design system, uli art, and Chinese Li art. The linearism that became evident in his art, especially in his drawings, outlined a stylistic phase that Oloidi (1993, p. 12) described as the "era of pictorial penmanship." The formal language employed by Udechukwu in these drawings is terse and stringent, yet lucid. It is also poetic, lyrical, and highly conceptual (Odoh, 2015). The works featured in his 1980 solo exhibition, No Water, emblematise this.

Udechukwu’s paintings, What the Weaver Wove (1992), Okochi (1993), Udummili (1993), Our Journey (1993), Landscape with Moon and Music, and The Prisoner (1994), foreground his status as an accomplished painter and colourist. His return to easel painting between the early and mid-1990s marked the last stylistic phase of his art practice while still living in Nigeria. Prior to this, he produced mostly drawings and prints. According to Udechukwu, "I am breaking away from black and white and moving back to painting and exploring other things, especially colour as colour, almost an end in itself" (Udechukwu et al., 2013, p. 519). In the paintings produced during this period, colour became more evocative, more eloquent, and more alluring. Other characteristics observable in his paintings include the compartmentalization of the pictorial surface, the simulation of texture using, the use of nuanced colour, and employment of sgraffiti technique as a pictorial device. Also, his themes, although retaining their socio-political activism, become more philosophical, revealing his in-depth knowledge of Igbo culture and worldview.

3.0 Framing Udechukwu’s diaspora artistic experiences

Prior to his diaspora status, Obiora Udechukwu had travelled abroad on numerous occasions to attend art exhibitions, conferences, workshops, and art residencies. These travels exposed him to different cultures and, as such, mitigated the level of culture shock that his relocation to the West could have caused. From Udechukwu’s point of view, considering his age when he left Nigeria and the deeply ingrained experiences of Nigeria’s socio-political, economic, and cultural environment, his experiences in the West are coloured by his life before his migration to the United States of America. He also notes that the digitalized global environment has enabled him to maintain his links in Nigeria (personal communication, October 13, 2013). However, Udechukwu admits that living in the United States of America for many years has created some ambivalences in his life and art (Udechukwu, 2003, para 1). Such ambivalences also draw from the circumstances that triggered the diasporic subject’s migration in the first place. Kasfir (1999, p. 190) points out some of these conditions as they relate to African artists:

The condition of displacement or exile is not simply the reverse of the romantic impulse that has propelled certain Western artists out of their own milieu into a more exotic one, but most often is a response by African artists to debilitating political repression or economic chaos at home.

The factors surrounding Obiora Udechukwu’s migration are closely linked to the conditions described above. In 1997, in the heat of a face-off with the University of Nigeria administration on matters of principle and moral justice, the artist, along with thirteen other academic colleagues, was suspended, placed on half pay, and subsequently detained, though temporarily, by the Nigerian police. Rather than succumb to intimidation or act against his principles, Udechukwu left the Nsukka art department, where he had taught for over two decades, and migrated to the United States of America.

In his seminal paper, "Whose Diaspora?" Tobias Wofford highlights the multitudinous challenges that frame the diaspora question. He notes that "an account of diaspora in any measure must be accompanied by the particularity of the diasporic subjects in question" (Wofford, 2016, p. 74). He equally notes that by paying "attention to the particular experiences of dispersal and the varying strategies of diaspora identity mobilized by each diasporic subject, a diaspora art history can indeed offer both insights and challenges to the historical analysis and narration of diversity in art and culture" (Wofford, 2016, p. 74). Kasfir (1999, p. 190) alludes to the experiences of dispersal as "a painful divorce or bereavement", an experience that she claims makes some migratory artists "remain firmly or tenuously attached to their former local, national or regional identities and traditions all their lives". She uses the Ethiopian artist Skunder Boghossian to illustrate this, noting that even though the artist taught for only four years in Ethiopia, he can still be categorized as an Ethiopian artist based on the cultural resources that his art draws upon (Kasfir, 1999). The act of appropriating cultural resources from the diasporic subject’s homeland brings into focus the question raised by Kishore Singh on whether art too has an ethnic identity because of the influence of the artist’s ethnic identity (as cited in Gleeson, 2016, para. 3). The subjectivities and particularities that frame diaspora experience and which consequently rub off on art produced by diasporic subjects are reflected in the views expressed by Farzin (2012, para. 7), who states, "What the work of the diaspora artist represents is primarily its own diasporic condition," performing "public gestures of belonging, staging its loss so as to overcome it through visual pleasure."

The denial, affirmation, and negotiation of identity are fundamental aspects of diaspora art. Sifting through their attendant rhetoric somehow raises questions about how memory, nostalgia, signs of difference, and desire, among other experiential factors, shape diaspora art. In questioning the place of memory and identity in diaspora art, Gleeson (2016, para. 5) inquires whether they should be seen as a burden, an advantage, a creative tool, or a combination of the three. Overlaying this line of thought on Obiora Udechukwu’s pre-diaspora art, as this will show, it is obvious that memory and identity are neither a burden nor a hindrance. At formal and thematic levels, a good number of Udechukwu’s works could be taken as acts of remembrance tapped from the chambers of memory. Evidences of this abound in his thematisation and the formal language used to address these themes. The works inspired by his experiences and memories of the Nigerian civil war are good examples.

Also, at personal and collective levels, his Dark Days Series memorializes the debasement of humanity by oppressive forces. Furthermore, the artist’s strong attachment to his Igbo roots, its culture, and its worldview functions as a cultural loom on which his memories of the homeland are woven into artistic currencies that are used for transacting identity in the global cultural arena. Obiora Udechukwu’s appropriation of Igbo culture and worldview in his art does not exclude a homogenous blending of other art cultures. He reiterates that his journey has been one of trying to find the appropriate idiom that effectively communicates his creative ideas. Drawing an analogy with the spirit with which European modernists borrowed from African sculpture and Japanese woodblock prints to revitalize their work and, by extension, their tradition, Udechukwu expresses his willingness to borrow from other art cultures as an avenue for advancing his work (Udechukwu et al., 2013). This process of assimilating certain elements of a new culture and fusing them with the already existing cultural values gives rise to what Udechukwu termed "the new traditional" (Udechukwu et al., 2013, p. 518).

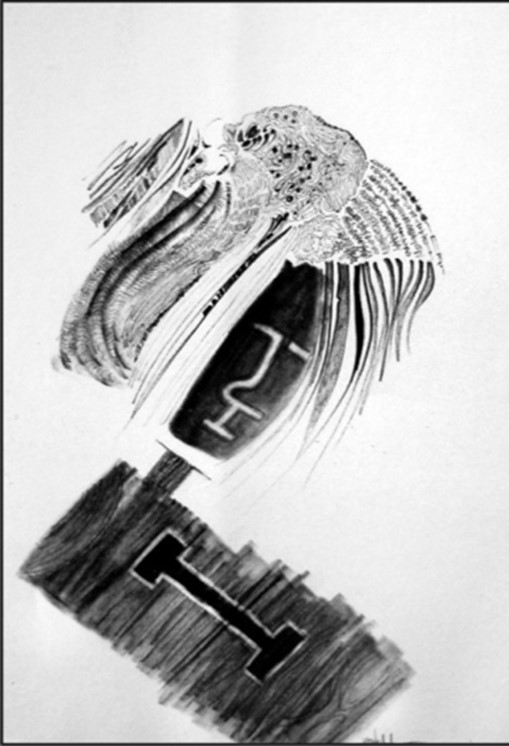

Apart from the installation, House of Truth, produced in 1998, Udechukwu’s diaspora art maintained the two-dimensional format that characterised his pre-diaspora art. His experimentation with colour as an end in itself, which marked the last phase of his studio practice in Nigeria, continued to influence his art in the diaspora. The paintings To Keep Nigeria One... (1997), In the Beginning (1998), Night Journey (2000), Memory: Moonlight Play (2005), Ezi n’ano (2006), and Ndidi (2010) show a formal relationship with other paintings produced by the artist in the early 1990s. His intense experience of colour is reinforced by the skillful deployment of pictorial devices that point out new directions in compositional structuring. For instance, in the work Ndidi (Figure 1), which addresses the virtue of patience, a theme that has been repeatedly engaged by the artist in the past, colour, texture, and text are employed as decorative and elocutionary devices to chart a new path in the artist’s approach to formal construction. The result is a seemingly mobile composition infused with energy, rhythm, and poetic essence. The composition comprises an abstract ink drawing of a fisherman angling for fish housed within the letter n. This linearity is also re-echoed in other parts of the painting by the wave-like patterns created with the sgraffito technique. The word ‘NDIDI’, boldly written and creatively arranged diagonally along the picture format, constitutes the major design element in the work. In the enclosed space within the letter ‘D’, Udechukwu incorporates text that addresses the theme. Also incorporated within the same space are bolder dark marks, some of which represent uli motifs like isinwaoji, okala isinwoji, and ntupo

Figure 1: Ndidi, 2010, acrylic and ink on canvas, dimension unknown.

© Obiora Udechukwu

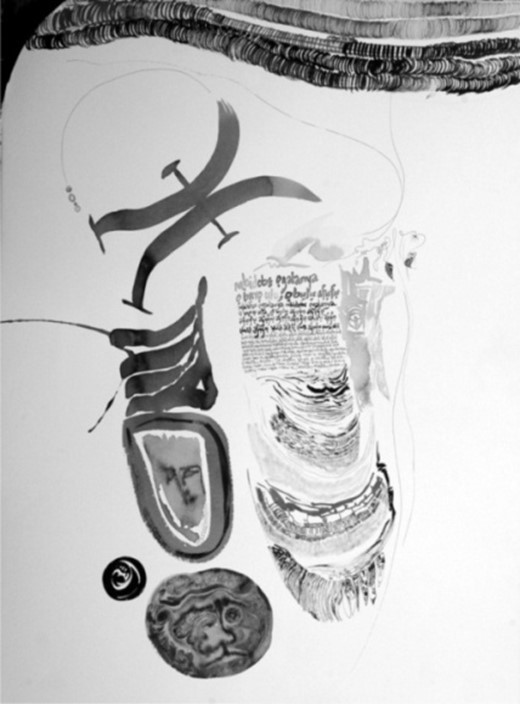

Stylistic shifts in Obiora Udechukwu’s diaspora art are much more obvious in his drawings. Compared to the formalism of the drawings that characterized the era of advanced linear oratory, his diaspora drawings are predominantly abstract, highly experimental, and very audacious in their line manipulation. Additionally, the themes become deeply philosophical, and texts feature more prominently as a critical design tool. His use of text takes on diverse roles. Not only do they act as communicative devices that reveal the artist’s thought patterns, but they are also used to define and decorate forms as well as to accentuate visual tension between positive and negative spaces. The works Nne Mmanwu (2000), Mother of all Drums (2000), Magic Birds (2005), The Face Behind the Mask (2004), and Face Behind the Myth II (2006) are emblematic of this stylistic shift. In Nne Mmanwu (Figure 2), the dominant image is a centralized portrait rendered with bold and thin lines, handwritten texts, as well as motifs derived from the nsibidi and uli design systems. The texts reference Igbo names that revolve around the concept of death. Conceptually, the piece could be read as a philosophical rumination on the demise of an iconic personality. The centralising idea draws from the feelings of nostalgia and sense of loss that are part of the diaspora experience.

Figure 2: Nne Mmanwu, 2000, pencil on paper, 29 x 23 cm. © Obiora Udechukwu

Contextually, Udechukwu’s strong attachment to his Igbo roots takes on a paradoxical role. On the one hand, it reminds him of the homeland he left behind—a world whose memories continuously create a psychological void that his adopted homeland can neither fill nor replace. On the other hand, through acts of remembrance and drawing from these memories, works such as Ndidi become therapeutic tools for relieving the sense of loss that his physical separation from his homeland inflicts on his psyche. Thus, Udechukwu’s continuous recourse to Igbo culture in his art could be viewed as a creative compass that allows him to express his ethnic and artistic identity in the global cultural arena. Given the peculiarities of its cultural, formal, aesthetic, and thematic signification, the upside of this creative disposition is that it somehow feeds into the position taken by Farzin (2012) as to what viewers expect of diaspora art, particularly its ability to bring to the fore the "viewer’s deep desires—for roots, for poetic depth, for historic and political relevance—and then resolves the traumatic backstory with a neat visual twist."

In terms of formal language, Magic Birds, Mother of all Drums, and Where Something Stands (Figures 3–5) show distinct stylistic traits in Udechukwu’s drawings. In Magic Birds, the approach is spontaneous yet reveals a sub-conscious control in the orchestration of unpremeditated lines. The centrality of line to this drawing, particularly in the treatment of the birds, infuses the work with a certain grace, lyricism, and expressiveness. The Mother of All Drums emphasises the combination of bold, dark tones with intricate linear forms. The interplay of these opposites creates strong tonal tension that provides the highpoint of the visual drama enacted by the dominant images of a woman’s face, the wooden gong, and the linear markings that define her hair. Where Something Stands reflects a minimalist approach that is not alien to Udechukwu’s art but is indicative of a much more austere treatment of visual elements. The theme's philosophical undertone, which references the belief that things come in pairs, provides an entry point through which its compositional framework could be understood; otherwise, the meagre ink marks may seem meaningless. Based on this, one begins to decipher the ink marks as a minimalist rendition of two figures, male and female, fused as one. Middle-toned ink brushwork consisting of three short horizontal and two vertical bands as well as a few dark-toned bands are strategically placed to establish the narrative. Other diaspora drawings by Udechukwu fall under these three stylistic approaches, although in some works like Rhythms of the Earth (2000), Anya Mmuo (2005), and Face Behind the Mask, one notices the fusion of the three stylistic frameworks.

Figure 3: Magic Birds, 2005, graphite on paper, 35.5 x 28 cm. © Obiora Udechukwu

Figure 4: Mother of all Drums, 2000, pencil on paper, 34 x 26.5 cm. © Obiora Udechukwu

Figure 5: Where Something Stands, 2005, ink and wash on paper, 38 x 28 cm. © Obiora Udechukwu

In 2005, Obiora Udechukwu explored a compositional framework that was distinctively different from previously known formats. The works that reflect this new approach, such as the Ofu n’Iru, Ofu n’Azu series, are viewed as units of expression, although they are actually executed on two different supports, canvas and paper, with the latter placed on top of the former. This compositional strategy was inspired by the Igbo saying, Ofu n'iru, ofu n'azu (One in front, one behind), a concept whose philosophical undertone parallels that of the earlier discussed drawing, Where Something Stands. The inspiration for the Ofu n'iru, Ofu n'azu series comes from a motif known as ofu n'iru, ofu n'azu, which is used by uli women painters to decorate walls. Udechukwu relates ofu n’iru, ofu n’azu to the concept of duality using the Igbo philosophy, Ọ na-abu ife kwulu, ife akwudebe ya (When one thing stands, another stands beside it), mentioned earlier. According to him,

If there is goodness, there is badness. If there is evil, it means there is good. This is also why our people will always look at both sides of every issue...So, for those works, the idea is that you can lift the first one to see the rest of the picture behind it. So, there is one on top and another behind that gives a completely different view. You know, quite often, people are told not to touch works of art, but in this case, you are free to touch the work, to demystify these things. (Personal communication, October 13, 2013)

Routes and Mmadu n’abo, uche n’abo (Two people, two different thoughts) are two works that exemplify the ofu n’iru, ofu n’azu concept. Both works are composed using two picture supports of unequal sizes, with the smaller one superimposed on the larger one. In Routes (Figure 7), a round-shaped face is depicted in the middle upper region of the smaller picture plane. The face has an enquiring gaze as if confused about where to go next. Perhaps this speaks to the feelings of anxiety and uncertainty that are usually experienced at crossroads. The compositional elements in the larger painting visually reinforce the idea of crossroads. Horizontal and vertical bands of green, purple, and dark brown hues separated by smaller white bands of even thickness are used to divide the pictorial surface into four major colour zones. The top left segment is rendered in blue, the top right in purple, and the lower left in black, while the lower right segment is rendered in yellow ochre and brown tones. Metaphorically, the different colour zones may allude to the varied outcomes arising from choices made at a crossroads. In some sense, Routes appear to reference the uncertainties that surround conditions of displacement, exile, or migration, especially for those diasporic subjects who had to make tough choices that warranted their leaving their respective homelands.

Figure 7: Routes, 2005 - 2006, acrylic on canvas, graphite on paper, 91 x 61 cm.

© Obiora Udechukwu

The underlying message in Mmadu n’abo, uche n’abo (Figure 8) is that no two people are alike and therefore have different thought patterns. Unlike in Routes, the compositional strategy employed in Mmadu n’abo, uche n’abo allows for a more open visual dialogue between the two painting supports. In the upper region of the light-toned smaller support, two irregularly shaped openings have been created, revealing the blue hue applied on the larger painting support behind. These two irregular shapes are the heads of two people. Their contrasting viewpoints are creatively suggested by the difference in the size, shape, and inclination of the abstracted heads. Texts that further amplify their different thoughts are strategically introduced into the composition to form the neck of the two individuals. The visible part of the painted support underneath shows patches of green, yellow, blue, and a much larger textured brown hue. The compositional ploy of concealing a major part of the painting underneath is aimed at making the viewer inquisitive and eliciting the urge to lift the composition above in order to view the hidden details. This makes the viewing process quite interactive.

Fig. 8: Mmadu n’abo, uche n’abo (Two Persons, Two Views), 2005 - 2006,

acrylic on canvas, graphite on paper, 91 x 61 cm. © Obiora Udechukwu

In the set of drawings that Obiora Udechukwu collectively titled Seville Drawings, his rendering of both controlled and spontaneous lines reinforces his experimental attitude in pushing the technical boundaries of his draughtsmanship skill. The drawings acquire their lyrical import through the systematic alignment of lines of similar length and thickness and also from the seemingly loose articulation of very elegant multi-directional lines. Two of the drawings (Figures 9 and 10) show extensive use of text in formal configuration. Some of the texts contain salient Igbo sayings that address general human conditions and also advocate the need for amity and harmony among the peoples of the world, irrespective of ethnic or gender differences. Udechukwu explains how concepts of peace and tolerance are addressed in the drawing shown in Figure 9:

If you look carefully at the work, there are two images. One is black, and the other one is white. It is actually the backside of human beings—the buttocks. This is taken from an Igbo saying which we hear quite often when people are getting married. People will say akpa ọhụ n’abo, nkụtụkọ, nkụtụkọ, onye akugbukwana ibe ya. So, the two parts of the buttocks as you walk each rub against the other, but they are not harming each other. (Personal communication, October 13, 2013)

Figure 9: Seville drawing, 2006, pen and ink wash,

dimension unknown. © Obiora Udechukwu.

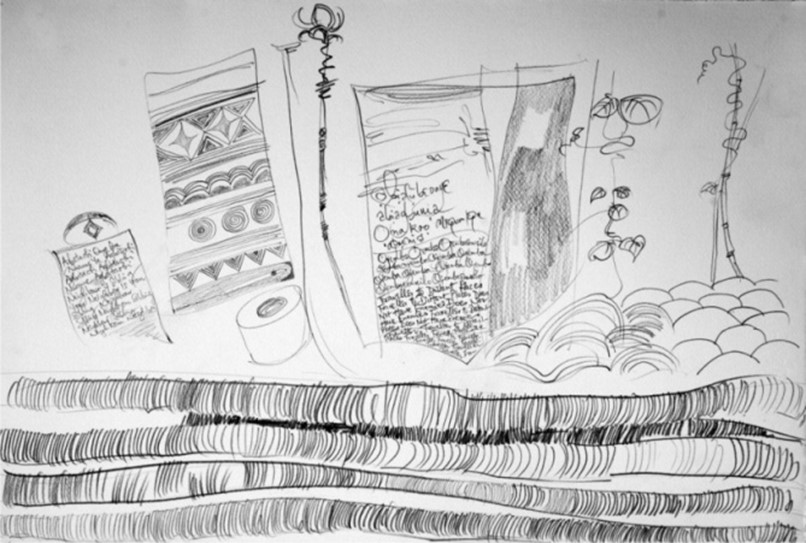

A deep sense of nostalgia is perceived in the drawing shown in Figure 10. On the left side of the composition is a Muslim slate with inscriptions. Udechukwu’s experiences of northern life when he was a student at Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, before the civil war seem to have inspired the use of this image. Beside the Muslim plate is a rectangular form that recalls the carved doors and panels in traditional Igbo societies decorated with uli motifs and designs. Below this structure is a roll of toilet tissue. Its presence in the composition is explained by the cubicle-like structure, which reminds one of the detached structures erected as bathrooms or toilets that are very common in Nigeria. In many Igbo communities, such structures are situated in farmlands close to the house. This explains the earth mounds with yam tendrils depicted on the right side of the composition. The distribution of these elements across the picture frame functions as narrative texts that memorialise Obiora Udechukwu's experiences of his homeland. Although these cultural tropes are quite removed from his adopted homeland, they are still vividly etched in his memory.

Figure 10: Seville drawing, 2006, graphite, dimension unknown.

© Obiora Udechukwu

Obiora Udechukwu’s Dark Days Series is an act of remembrance that narrates painful and unpleasant ordeals. Some of the works that constitute the series are visual autobiographies of Udechukwu’s personal experiences that he uses to address universal issues of confinement and debasement. The artist links the Dark Days Series to Kwame Nkrumah’s book, Dark Days in Ghana, which recounts Nkrumah’s experience when he was overthrown by reactionary forces. He uses one of the works in the Dark Days Series to highlight the tragedy of the human condition:

…Although the picture references a specific and tragic period in the history of Nigeria, it transcends that. The work looks back several centuries to the infamous Middle Passage, in which millions of Africans were transported in unspeakable conditions from the continent to the Caribbean and the United States to work as slaves on plantations. In the 1990s, the military government in Nigeria treated people in much the same way, locking large numbers of citizens in overcrowded cells without trial. At a personal level, I was incarcerated by the Nigerian military government in 1997 for some weeks, along with other academic colleagues. So, there is a link. I take the particular and use it to address the general. As far as I am concerned, human beings have not changed. Human beings have not changed at all. (Udechukwu, 2003, para.2)

In the painting Dark Days (Figure 11), images alluding to confinement and oppression are depicted using muted colours comprising varying tones of grey, black, yellow, and blue hues. The chaotic brushwork used in rendering these moody tones evokes a feeling of restlessness. This agitated zone surrounds a partially cut circular shape trapped at the angle between the two lower edges of the picture format. The area enclosed by the circular shape is the zone of confinement. Within this confined space are tightly packed human figures in discomfiting positions. In addition to evoking a heightened feeling of claustrophobia, their poses and distribution also evoke feelings of deprivation and dehumanization. The black area at the top of the composition functions as a wall that symbolises captivity. The barred entrance, which further re-echoes a state of confinement, also offers hope for freedom. This is illustrated by the six rainbow-like reflections of sunlight streaming into the cell. One can link the experiences portrayed in the Dark Days series to the diaspora experience, especially the socio-political and cultural restrictions often encountered by diasporic subjects that are capable of triggering feelings of psychological confinement, resentment, and debasement.

Figure 11: Dark Days, 2003, acrylic, dimension unknown.

© Obiora Udechukwu

The installation, House of Truth (Figure 12), highlights the post-modernist side of Obiora Udechukwu’s art practice. He had earlier explored this mode of representation in the project House of Four Trees, executed in Germany in 1995. The House of Truth was his contribution to a conference that addressed the issue of war, particularly in Bosnia and other countries experiencing wars and conflicts. The project focused on the Nigeria-Biafra civil war and military rule in Nigeria. In addressing the theme, the installation engaged the concept of truth using architecture, visual arts, literary arts, and performing arts as compositional elements. The structure was built in such a way that people could interact with it both from the outside and within. The interior contained Udechukwu’s works produced at different periods in his career as well as the works of other Nigerian artists, including Boniface Okafor and Kevin Echeruo. Visitors were encouraged to play participatory roles. They made marks on their faces with chalk before entering the structure to view the artwork within. Provision was also made for them to make comments and contributions by writing or painting on the inside walls. In addition to the other pictorial devices employed in the installation, Udechukwu introduced enormous volumes of texts, which he explains were taken from several poems and presented in reverse form so that to properly read the poems, one had to look into a big mirror placed directly in front of the work (Personal communication, October 13, 2013).

Fig. 13: House of Truth, 1998, installation. Source: Chika Okeke-Agulu

Another strategy employed by Udechukwu is the use of numerous linear markings, designs, and motifs found in traditional uli art in decorating the exterior and interior walls of the structure. The colours used also reflect the uli palette, which comprises red, yellow ochre, black, white, and indigo hues. By making the uli idiom an important feature of the installation, Udechukwu symbolically highlights the disruptive nature of war on a people’s way of life—in this case, that of the people of south-eastern Nigeria, in whose territory the civil war was mainly fought. Although conceived as an installation, House of Truth mirrors some of the stylistic frameworks found in Udechukwu’s two-dimensional art. Some of the issues that frame the theme addressed in House of Truth, such as displacement, migration, exile, memory, acts of remembrance, nostalgia, and identity, are also critical to the diaspora experience.

4.0 Conclusion

The perceptible absence of themes that address the sociopolitical and cultural experiences of his adopted country in Obiora Udechukwu’s diaspora art offers insights into some of the ways diasporic artists work through diaspora experiences in their art. This opens up critical spaces in which to further interrogate the influence of diaspora experience on visual art practice. As the study reveals, Udechukwu’s diaspora art practice has remained tethered to the dominant factors that framed his art practice when he was still living in Nigeria. These include his deep-rooted interest in Igbo culture and worldview, his use of a highly linear artistic language that draws from the extensive use of the formal and aesthetic codes of uli art and nsibidi design systems as compositional devices, the resistance outlook of his sociopolitical commentaries, and the recurring reference to his personal experiences and memories of the Nigeria-Biafra civil war.

Reflecting on the diaspora experience, Udechukwu is of the view that diasporic subjects should make sure that their children know their stories and their histories (Udechukwu, 2003, para 3). However, despite his persistent artistic gaze towards his homeland, he is still aware of the influence of cross-cultural encounters on his diaspora experience. He acknowledges that one is part of the society where one lives (Udechukwu, 2003), although as a diasporic subject, it is quite difficult for him to identify where this is visibly expressed in his art (personal communication, October 13, 2013). Obiora Udechukwu believes that "tradition is complex, flexible, and multi-layered—both horizontally and vertically" (Udechukwu et al., 2013, p. 519) and that it opens the door for a traveler to assimilate new elements from other locations and fuse them with the familiar. Moving forward, the artist has the conviction that his art will continue to pay respect to the past and will equally be driven by an awareness of self and his specific location, both temporally and geographically (Udechukwu et al., 2013). In keeping with this conviction, Udechukwu draws from the chambers of memory as well as from the pool of cultural and ancestral knowledge and, through acts of remembrance enacted on two-dimensional surfaces, interrogates both the ambiguities and ambivalences of contemporary experiences. He sees his art as the subconscious side of him working in concert with the deliberative or intellectual (Udechukwu et al., 2013, p. 519).

Noticeable stylistic shifts have occurred in Obiora Udechukwu’s diaspora art. For instance, his drawings have become more sophisticated in terms of their sublime linear language, their exquisite and dynamically structured compositions, and the artist’s impressive sub-conscious control in the orchestration of premeditated and unpremeditated lines. This is emblematised by Magic Birds (see Figure 3). Also, text has assumed a commanding presence in his works and functions as both communicative and decorative elements. Furthermore, his diaspora art practice reveals the development of a design strategy that combines two different pictorial supports in one work, with the smaller support placed on top of the larger support. This makes viewing the work interactive, as viewers are allowed to lift the composition on top to reveal what is beneath.

Placed in its proper historical context, Obiora Udechukwu’s diaspora art provides a progressive reading of his progressive reading of the art career of one of the most influential artists of the Nsukka Art School. In 2015, the Faculty of Arts of the University of Nigeria organized Anya Fulu Ugo, an international conference and exhibition, to honour Udechukwu and El Anatsui, another prominent artist of the Nsukka Art School. This celebratory gesture acknowledges Udechukwu’s critical interventions in contemporary art practice—lasting legacies that transcend the frontiers of his homeland.

References

Agbayi, E. (2003). Homage to Asele and art in Nigeria: A contemplative discourse. In Homage to Asele (exhibition catalogue), pp. 7-12. Enugu: Pendulum Art Gallery.

Aniakor, C. (1987). Aka: A second season of harvest. In Aka 87 (exhibition catalogue), pp. 5-8. Enugu: Aka Circle of Exhibiting Artists.

Farzin, M. (2012). The imaginary elsewhere: How not to think of a diasporic art. Retrieved from https://www.bidoun.org/articles/the-imaginary-elsewhere

Gleeson, B. (2016, November 1). An Intriguing Group Show Explores the Ethnic Identities of India’s Diaspora Artists. Artsy. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-an-intriguing-group-show-explores-the-ethnic-identities-of-india-s-diaspora-artists

Ikwuemesi, K. (1992). Uli as a creative idiom: A study of Udechukwu, Aniakor and Obeta (Unpublished B.A. Thesis), Department of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Nigeria, Nsukka.

Kasfir, S. (1999). Contemporary African art. London: Thames and Hudson.

Nwafor, O. (2005). Uli as poetry. In K.Ikwuemesi & E. Agbayi (Eds.), Uli and the politics of culture (pp. 43-52).Enugu: Pendulum Centre for Culture and Development.

Odoh, N. S. (2015). Art professionalism, shifting identities and creative correspondences in the art of Obiora Udechukwu (Unpublished doctoral dissertation), Department of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Nigeria, Nsukka].

Ofoedu-Okeke, O. (2012). Artists of Nigeria. Milan: Five Continents Editions.

Okpewho, I. (1997). Foreword. In S. Ottenberg (Ed.), New traditions from Nigeria: Seven artists of the Nsukka group (pp. ix-xiv). Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Oloidi, O. (1993). Obiora Udechukwu: Fulfilled but still after clarity of vision. In So Far (Exhibition catalogue). Bayreuth: Boomerang Press.

Ottenberg, S. (1997). New traditions from Nigeria: Seven artists of the Nsukka group, Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Udechukwu, O. Brewer, J., Clarke, J. A., Guha-Thakurta, T., Hayden, H., Horowitz, G. M., Kaufmann, T.D., Küchler, S., Loh, M. H., Phillips, R. B., Prange, R. & Russo, A. (2013). Notes from the field: Tradition, The Art Bulletin, 95(4), pp. 518-543. DOI: 10.1080/00043079.2013.10786091

Udechukwu, O. (2003). Lines of migration: Paintings by Kenwyn Crichlow and Obiora Udechukwu. Available from http://web.stlawu.edu/gallery/exhibit-s03.htm

Windmuller-Luna, K. (2014). A Nigerian song literatus: Chinese literati painting concepts from the Song Dynasty in the contemporary art of Obiora Udechukwu. Rutgers Art Review, 29, pp. 61-83. Available from https://princeton.academia.edu/KristenWindmuller

Wofford, T. (2016). Whose Diaspora? Art Journal, 75(1), pp.74-79. DOI: 10.1080/00043249.2016.1171542

Wolf, R. (2014). The memory of the Nigerian civil war in the art of Obiora Udechukwu. Interventions,3(3). Retrieved from http://interventionsjournal.net/2014/07/03/the-memory-of-the-nigerian-civil-war-in-the-art-of-obiora-udechukwu-2/