Associate Professor 2, Jose Rizal Memorial State University, Philippines

DOI: 10.55559/sjahss.v2i04.99 | Received: 24.03.2023 | Accepted: 03.04.2023 | Published: 07.04.2023

ABSTRACT

Language learning requires strategies that increase our competence in communication. This study identified the language learning strategies and the grammatical competency level of the Bachelor of Secondary Education (BSED) English major students at Jose Rizal Memorial State University (JRMSU), School Year 2017-2018. This research is mixed methods since it determined the language learning strategies mostly used by the students and identified the grammatical competency level of the respondents. The researcher triangulated the data from the survey using the focus group discussion through semi-structured interviews. It further examined whether there is a significant relationship between language learning strategies and the grammatical competence level of the BSED-English. The respondents of this study were the 138-3rd year BSED-English major students of JRMSU chosen through simple random sampling by the lottery technique. The students took the Strategy Inventory of Language Learning (SILL) survey questionnaire, developed by Oxford (1990), and the grammatical competence test. Twelve students from the group participated in the focus group discussion. The data were checked, tallied, and analyzed utilizing the weighted mean, ranking, and percentage. The researcher employed Spearman's Rho test to find the relationship between language learning strategies and grammatical competency levels. She then transcribed and coded the data from the focus group discussion. The results of this study showed that language learning strategies usually used by the BSED-English major students were metacognitive, social, cognitive, affective, and compensation strategies. In addition, it showed that the overall grammatical competence level of the students is competent, which revealed their higher competence level in word formation and syntax but less competence in spelling, pronunciation, and vocabulary. The results showed a significant relationship between language learning strategy use and grammatical competence level, indicating that the more language learning strategies are mostly used by the students, the higher their grammatical competence level.

Keywords: language learning strategies, grammatical competence, metacognitive strategies, word formation, syntax

|

Electronic reference (Cite this article): Rodriguez, E. (2023). Language Learning Strategies and Grammatical Competence of the English-Major Students in Zamboanga del Norte HEIs. Sprin Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, 2(04), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.55559/sjahss.v2i04.99 Copyright Notice: © 2023 Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license. |

1.0 Introduction

Learning is a continuing process gained through the interaction of study, instruction, and experience (Francis & Rivera, 2007). Learning strategies are ways taken by students to improve their learning. Strategies are especially significant for language education since they aid in active, self-directed involvement, which is extremely important for developing communicative competence. According to Oxford (1990), suitable language learning strategies improve proficiency and self-confidence.

One of the most critical issues for educating English Language Learners (ELLs) is their dearth of academic language skills needed for school achievement (Scarcella, 2003; Bailey & Butler, 2007). A lack of academic language proficiency affects the ELL's capability to comprehend and analyze texts in middle and high school, restricts their ability to write and express themselves effectively, and can hamper their gain of academic content in all academic fields. Moreover, in light of the role of vocabulary and grammar in educational content zones, ELLs face difficulties in acquiring content area knowledge: their academic language and, therefore, achievement lags behind that of their native English-speaking peers (National Center for Education Statistics, 2005).

Thus, it is relevant to give special attention to the learning strategies of each student that can work together with - or in conflict with - a given instructional methodology. Oxford (2003) hypothesized that if there is a balance between the student's strategy preferences and the fusion of instructional methods and materials, students are likely to perform well, feel confident, and experience low anxiety. Conversely, if clashes occur between these factors, the students often perform poorly, feel diffident, and experience significant anxiety. Sometimes, such disagreements lead to a severe breakdown in teacher-student interaction. These conflicts may also lead to the depressed student's outright rejection of the teaching methodology, the teacher, and the subject matter.

Equally important as the language learning strategies is grammatical competence as part of communicative competence. According to Diaz-Rico and Weed (2010), communicative competence is a function of the language awareness of a language consumer, which helps the consumer to know when, where, and how to use language correctly. Grammatical competence is one of the four areas of the communicative competence theory by Canale and Swain (1980).

Grammatical competence focuses on the command of the language code, including the rules of the shape of terms and sentences, names, spellings, and pronunciations (Gao, 2001). The goal is to gain awareness of and the capacity to use grammatically appropriate and consistent modes of speech (Diaz-Rico & Cannabis, 2010; Gao, 2001). Grammatical abilities encourage consistency and fluency in second-language development (Gao, 2001) and rise in value as the learner progresses (Diaz-Rico & Weed, 2010). Grammar skills grow in value as the learner progresses in skills (Diaz-Rico & Weed, 2010).

As students travel through the stages of language proficiency, grammatical competence becomes more critical since grammar is the glue that binds the English language together (Gaard, n.d.). That is why it is necessary to determine the language learning strategies the BSEd English major students use to examine their English language deficiencies, especially in grammar. In the previous study conducted by the researcher and her co-author on evaluating the weakness of the graduates of the JRMSU-Tampilisan Campus concerning the DepEd requirements in hiring teachers, Liboon and Rodriguez (2017) found that the graduates are most deficient in terms of teaching experience, followed by the English Proficiency Test (EPT) (Liboon & Rodriguez, 2017) as conducted with the Bachelor of Elementary Education (BEED) graduates LET passers who applied for Teacher I position in DepEd Zanorte.

On the other hand, the Bachelor of Secondary Education major in English (BSEd-English) is a four-year degree program that will prepare students for teaching English subjects in high school offered by the JRMSU system. Based on the researcher's observation, the college students in the institution performed poorly in writing composition, evident in their grammatical errors committed.

Another problem the school faces is the low Licensure Examination for Teachers (LET) rating. For the past few years, the JRMSU-TC LET passing rate was always below the National Passing Rate set by the Philippine Regulation Commission (PRC). The College of Education in JRMSU-Tampilisan Campus, during September 2016 LET, registered only 17 out of 92 takers, or 18.48%, while BSED recorded only six from the 102 takers, or 5.88% (The State Collegian, 2017).

With the above premises, this study assessed the language learning strategies mostly used by the JRMSU BSED-English major students and their grammatical competence level. Specifically, the study aimed to 1) identify the language learning strategies mostly used by the JRMSU major in English students in terms of Memory strategies, Cognitive strategies, Compensation strategies, Metacognitive strategies, Affective strategies, and Social strategies; 2) determine the grammatical competency level of the JRMSU BSEd English major students in terms of Pronunciation, Spelling, Word Formation, Syntax, and Vocabulary; 3) determine whether there is a significant relationship between the Language Learning strategies and the Grammatical Competency Level of the BSEd, English major students in JRMSU.

2.0 Objectives of the Study

This study aimed to identify the language learning strategies mostly used by the JRMSU BSED-English major students and their grammatical competency level.

Specifically, the study sought to answer the following questions:

3.0 Theoretical/Conceptual Framework

This study is anchored on the Theory of Oxford (1990) on Language Learning Strategies as well as on Grammatical Competence as one of the areas of Canale and Swain’s (1980) Communicative Competence.

Oxford (1990) developed a comprehensive classification system of learning strategies using two major groups: direct and indirect strategies. Each category was broken down into subcategories reflecting the specific strategies that would fit under the labels. For example, direct strategies, which are directly related to learning/producing the target language, are subdivided into Memory strategies (retrieving and storing new information), Cognitive strategies (operating new input), and Compensation strategies (overcoming missing knowledge of a target language).

Indirect strategies are those that enable direct strategies to occur and/or increase their successful application. Indirect strategies include Metacognitive strategies for managing the cognitive process, Affective strategies for controlling emotions in language learning, and Social strategies for interacting with others. In general, these strategies help students (a) to become more autonomous, (b) to diagnose their learning strengths and weaknesses, and (c) to self-direct their learning process (Oxford, 1990). Learning strategies, therefore, help learners become efficient in learning and using a language.

In Canale and Swain’s (1980, 1981) model, grammatical competence is mainly defined in terms of Chomsky’s linguistic competence, which is why some theoreticians (e.g., Savignon, 1983), whose theoretical and/or empirical work on communicative competence was largely based on the model of Canale and Swain, use the term linguistic competence for grammatical competence. According to Canale and Swain, grammatical competence is concerned with mastery of the linguistic code (verbal or non-verbal), which includes vocabulary knowledge and knowledge of morphological, syntactic, semantic, phonetic, and orthographic rules. This competence enables the speaker to use the knowledge and skills needed for understanding and expressing the literal meaning of utterances.

The independent variable of this study consists of the six major groups of second language learning strategies identified by Oxford (1990). These are memory strategies, cognitive strategies, compensation strategies, metacognitive strategies, affective strategies, and social strategies, which are hypothesized to have a significant association with the grammatical competency level in any of the sub-variables, such as pronunciation, spelling, word formation, grammar, and vocabulary.

The types mentioned above of language learning strategies are assumed to have a significant association with the grammatical competence level based on what was revealed in the studies previously discussed in this paper.

4.0 Methodology

The current study employed a mixed-methods design, including quantitative and qualitative research methods. According to Creswell (2003), this is "an inquiry strategy that is focused on converging or triangulating different quantitative and qualitative data sources" (p. 210). The design combined both approaches, offering a much more accurate and informative picture of what was discussed in the study. The researcher utilized something similar to what Creswell (2003) called a sequential explanatory model, a mixed-method design in which quantitative data collection was undertaken before qualitative data collection. With the priority being placed on the quantitative data (a questionnaire was given to the whole sample), the qualitative data (interviews conducted with a subsample) were used to explain and elucidate the quantitative data, thus deepening the understanding and interpretation of the results.

This study employed three instruments to gather the data needed. These were the Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL), the Grammatical Competency Test, and the Focus Group Discussion. The first instrument used in this research is a survey questionnaire Oxford developed in 1990 called Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL). It is a self-report, paper, and pencil survey. The SILL was initially designed to assess the frequency of use of language learning strategies by students at the Defense Language Institute in California. Two versions of the SILL were available in Oxford's (1990) language learning strategy book for language teachers. The first is used with foreign language learners whose native language is English, containing 80 items. English learners use the second test as a second or international language. It consists of 50 items. This study used the latter variant. Oxford and Burry-Stock (1995) asserted that the results of the studies regarding the reliability of the ESL/EFL SILL have shown that it is a highly reliable instrument. Concerning the content validity of the inventory, Oxford and Burry-Stock (1995) stated that the instrument's content validity was determined by professional judgment and was found to be very high. The SILL (Version 7.0) consists of six subsections. Each section represents one of the six categories of LLS, which the learners do not know when taking the inventory. The 50 statements in the list follow the general format 'I do such and such.' Students respond on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1, 'Almost never true of me,' to 5, 'Almost always true of me.'

The current study required the participants to circle the number corresponding to the survey questionnaire's answer. Upon completing all the answers, the values assigned to each item in each section have been added and then divided into the number of items in each section. The same procedures were repeated for each section, and values between 1 and 5 were obtained. These values showed the profile of a learner; in other words, the strategy groups employed by the learner and their frequency. The second instrument was used to determine the level of grammatical competence of the BSED-English major students. The Grammatical Competence Test was adapted from different online resources. The competency test is made up of multiple sections, each comprised of 20 items. This test included pronunciation, spelling, word formation, syntax, and vocabulary. The third instrument is the question guide for the Focus Group Discussion in the form of a semi-structured interview. It listed seven questions regarding the language learning strategies used by the students. The first instrument, the Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL) developed by Oxford (1990), was considered valid since it is a standardized survey questionnaire. However, it was administered to the 3rd year BSED-English major students who were not participants in the study to test its reliability. Nevertheless, the SILL survey was highly reliable since its Cronbach’s Alpha was .95.

Meanwhile, the panel of experts corrected and validated the grammatical competency test before administering it to the respondents. The validators qualified the items to be included and those to be rejected or revised. It was then pilot tested with the 3rd year English major students at Saint Joseph College of Sindangan. The pilot test result was later subjected to item analysis. The test did not include items that were found to be very easy and most difficult. Some statements were revised, and the majority were accepted.

The study was conducted at the four different campuses of Jose Rizal Memorial State University, Zamboanga Del Norte, particularly in the College of Education of each campus: Dapitan, Dipolog, Tampilisan, and Siocon. The study's respondents were the Bachelor of Secondary Education (BSED) major in English students from the College of Education of each campus. Meanwhile, the FGD participants were taken from the BSED-English major of Tampilisan Campus only since it was financially unfeasible to collect data from the four schools and beyond the time allotted by CHED to complete the study.

The respondents of this study were the 138-3rd year BSEd English major students of Jose Rizal Memorial State University during the 2nd Semester, School Year 2017-2018. These students were enrolled in January 2018 since the institution is an August starter due to the ASEAN 2015 Integration. These 3rd-year BSED-English students of JRMSU had passed the major English courses such as Language and Curriculum for Secondary, Afro-Asian Literature, Literary Criticism, American Literature, Teaching of Listening and Reading, and Mythology and Folklore. In addition, the participants of this study had also taken their Structure of English course. Thus, it was relevant to determine their grammatical competence in pronunciation, spelling, word formation, syntax, and vocabulary. Furthermore, this study was conducted at the 3rd year college level since the data collection started. The four mentioned schools did not have 1st- and 2nd-year BSED-English enrollees due to the K to 12 Transition Period.

There is a 138 or 64% sample size from the 214-total number of 3rd-year BSED-English students enrolled in the 2nd Semester of School Year 2017-2018. The 64% sample size was determined using a sample size calculator with a 95% confidence level. After determining the 64% sample in each campus, the respondents for this study were selected using probability sampling, particularly simple random sampling using the lottery technique, to have an equal chance to participate in the survey and test.

For the data collection, first, the researcher sought permission from the President of the JRMSU System, different Campus Administrators, and the various Deans of the College of Education of the four JRMSU campuses. After the consent was granted, the researcher informed the Campus Administrator, the Registrar, the Dean of the College of Education, and the BSED Program Chair of each campus regarding the study. Then, the schedule was arranged for when to administer the survey questionnaire and the grammatical competence test. When the negotiation was finalized, the researcher conducted the study. The respondents were given 20-30 minutes to answer the SILL survey, which was immediately retrieved so that they could proceed to the grammatical competency test. After that, they were allotted one and a half hours to finish the grammatical competency test, which has five parts, namely: pronunciation test, spelling test, word formation test, syntactic test, and vocabulary test. After conducting the SILL and the test on grammatical competence in the four campuses, the Focus Group Discussion (FGD) followed. Due to budgetary constraints, the 12 FGD participants from JRMSU-Tampilisan BSED-English students were chosen. However, the 12 participants were still selected using the lottery technique, and they were from the 25 students of JRMSU-Tampilisan who took the SILL. The FGD was in the form of a semi-structured interview. The researcher acted as an interviewer, and she requested two facilitators to help: one as secretary and the other was assigned to the audio recording of the session. The survey and test results were checked, tallied, and interpreted. In contrast, the results of the FGD were transcribed and coded according to the language learning strategies indicated in the SILL instrument.

In finding the Language Learning Strategies mostly used by the JRMSU English major students in terms of memory, cognitive, compensation, metacognitive, social, and affective strategies, the weighted mean and ranking (Zhou, 2010) were utilized with a qualitative description within the established limits as follows:

| Weight | Range of Values | Description |

| 5 | 4.50-5.00 | Almost always used (AU) |

| 4 | 3.50-4.49 | Usually used (UU) |

| 3 | 2.50-3.49 | Sometimes used (SU) |

| 4 | 1.50-2.49 | Generally not used (GnU) |

| 1 | 100-1.49 | Almost never used (NU) |

In identifying the level of grammatical competence of the BSED-English major students, frequency counts and percentages were employed. The grammatical competency test scoring followed the 50% passing (raw score x 50 / total no. of items + 50 = rating or grade) based on the JRMSU Grading System (JRMSU Code, 2017). The following rating scale was adopted to identify the grammatical competence level of the BSED-English students.

| Rating Scale | Description | Code | (JRMSU Grading System) |

| 99.00 - 100.00 | Highly Competent | (HC) | (Excellent) |

| 91.00 - 98.99 | Much Competent | (MC) | (Very Good) |

| 80.00 - 90.99 | Competent | (C) | (Good) |

| 75.00 - 79.99 | Less Competent | (LC) | (Fair) |

| 74.00 and below | Not Competent | (NC) | (Failed) |

In determining the significant relationship between the Language Learning Strategies and the Grammatical Competency level of the BSEd English Major Students, Spearman's Rho, with the aid of Stata, was employed since this study tested the non-parametric correlation of variables.

Open coding was employed to analyze the focus group discussion result. First, the researcher read through the data several times and then created tentative labels for chunks of data summarizing the results. Next, the researcher recorded examples of participants' words and established properties of each code, whether the sub-strategies they were using fell on memory, cognitive, compensation, metacognitive, affective, and social strategies.

5.0 Results and Discussion

The language learning strategies used by the BSED-English major students of Jose Rizal Memorial State University, Zamboanga del Norte, are shown in Table 1. The result indicates that the BSED-English major students of JRMSU usually used sub-strategies that fall under the metacognitive strategies, such as centering, arranging, planning, and evaluating their learning. In addition, they also utilized social strategies such as asking questions, cooperating, and empathizing with others. Likewise, the students employed mental or cognitive strategies such as practicing, receiving, sending messages, analyzing and reasoning, and creating structures for input and output.

Meanwhile, these students also used sub-strategies such as managing emotions by lowering their anxiety, encouraging themselves, and taking emotional temperature, which fell under the affective strategies. They also utilized strategies to make up for missing knowledge, such as guessing intelligently and overcoming limitations in speaking and writing, which are the compensation strategies.

Table 1

Language Learning Strategies Mostly Used by the JRMSU BSED-English MajorStudents

|

Language Learning Strategies |

Weighted Mean |

Rank |

Description |

|

Memory Strategies Cognitive Strategies Compensation Strategies Metacognitive Strategies Affective Strategies Social Strategies |

3.45 3.80 3.61 4.07 3.65 3.91 |

6th 3rd 5th 1st 4th 2nd |

Sometimes Used Usually Used Usually Used Usually Used Usually Used Usually Used |

|

Overall Mean |

3.75 |

Usually Used |

Legend: Range of Values Description

4.50 - 5.0 Almost always used

3.50 - 4.49 Usually used

2.50 - 3.49 Sometimes used

1.50 - 2.49 Generally not used

1.00 - 1.49 Almost never used

In general, the respondents of this study "usually used" the language learning strategies, which implies that the students pay attention, consciously search for practice opportunities, plan for language tasks, self-evaluate their progress and monitor their errors. They likewise ask questions, communicate with others using the English language, and become culturally aware of other people's cultures. The students also reason, analyze, and summarize - all reflective of deep processing. They also reduce anxiety, encourage themselves, and do self-reward. They, too, guess meanings from the context of listening and reading and use synonyms and gestures to convey a meaning when the precise expression is not known. The JRMSU BSED-English major students employed the abovementioned strategies in learning the second language.

These findings are supported by the focus group discussion data, whereby the students asserted that they sometimes do memorization. For example, when they find new words, they use them in a sentence or write in their vocabulary notebook for them to look for their meanings in a dictionary. The respondents also scanned before skimming and looking for the text's main idea. Likewise, they do silent reading to comprehend the passage before reading it loudly to practice pronunciation. Meanwhile, when they become speechless in a conversation, they try to use sign language, gestures, and facial expressions. They also use words synonymous with what they have to say with word association.

The BSED-English major students affirmed that they usually watch English movies with subtitles to help them understand fully the lines of the characters, which results in their language learning, studying the grammatical rules of the English language and trying to identify errors in a written text, read books with a dictionary at hand and check the meaning of the problematic words encountered if using context clues could not help them and practice speaking the English language in front of the mirror. Besides, they read books, English novels, and stories written in English and try to use a second language whenever they have conversations with friends and peers. In using English in communications, the respondents overcome anxiety by taking deep breaths and trying to relax and be calm, confident, and optimistic about accepting criticism. They also search online and watch English movies to learn more about American culture and the target language.

The above finding corroborates the study of Hong-Nam and Leavell (2006), who found that the students preferred to use metacognitive strategies mostly. In contrast, they showed the least use of affective and memory strategies. They have executive control over the learning process since the metacognitive strategies are mostly behaviors used for centering, arranging, planning, and evaluating their learning. These are "beyond the cognitive" strategies (Akbarov & Arslan, 2010, p. 16). Likewise, Al-Qahtani’s (2013) study showed that her respondents utilized all language learning strategies, and cognitive strategies were the most frequently used. Yaimin's (2006) research also found that the pupils employed cognitive strategies in learning English with the highest total average of 3.50. The other strategies employed were the metacognitive strategy, affective strategy, memory strategy, social strategy, and compensation strategy. Both studies indicate the students' skills, which involve manipulation and transformation of language in the same direct way, such as note-taking, functional practice in naturalistic settings, formal training with structures and sounds, as well as through reasoning analysis.

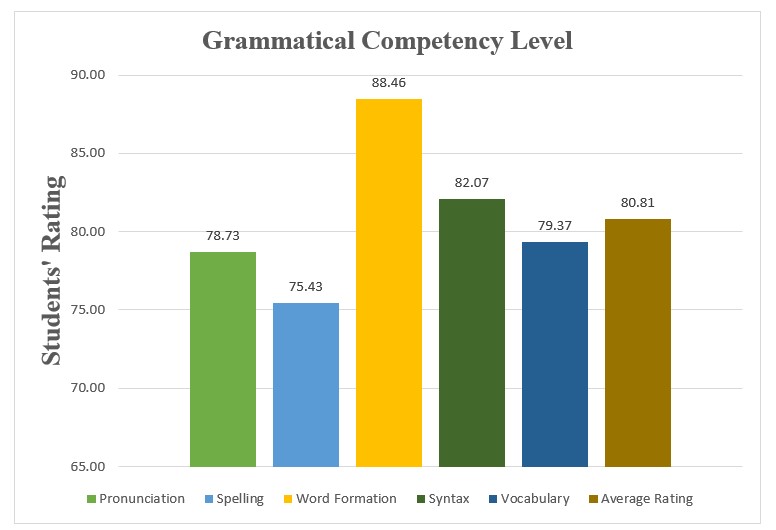

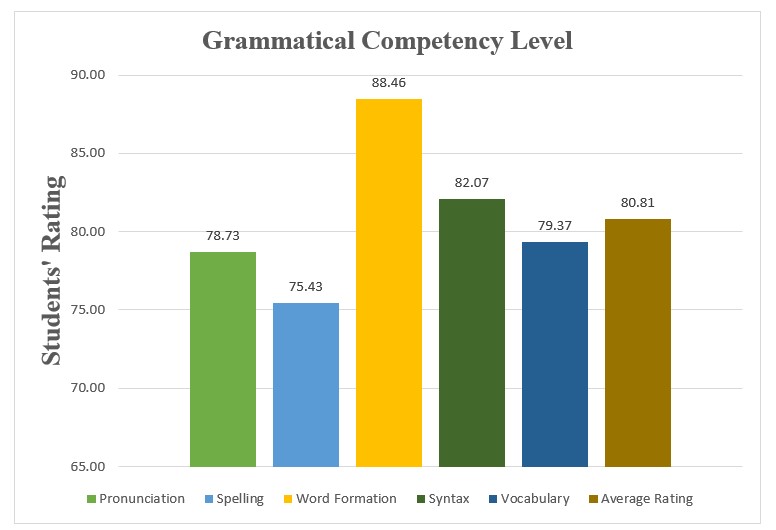

Figure 1. The grammatical competence level of the JRMSU BSED-English major students

|

Legend: |

Rating Scale |

Description |

|

|

99.00 - 100.00 |

Highly Competent ( HC ) |

||

|

91.00 - 98.99 |

Much Competent ( MC ) |

||

|

80.00 - 90.99 |

Competent ( C ) |

||

|

75.00 - 79.99 |

Less Competent ( LC ) |

||

|

74.00 and below |

Not Competent ( NC ) |

||

Figure 1 shows the grammatical competency level of the JRMSU BSED-English major students. The respondents here are seen to be "competent" in word formation and grammar. It means that the students are competent in creating new words based on other words or morphemes, also called derivational morphology. Likewise, they are also skilled in encoding meanings into words in English, which include the structure of words, phrases, clauses, and sentences up to the construction of the whole text.

Meanwhile, the respondents were "less competent" in vocabulary, pronunciation, and spelling. These results mean that the students were less competent in a vocabulary test intended to look into their range (or stock) of words. The respondents were also less confident in pronunciation practice, which examined how the students tried to pick the correct sound output of the given words based on the phoneme. Likewise, the students were less competent in the spelling test, meaning they could not recognize the correct spelling of the words when given options.

On the whole, the grammatical competency level of the BSED-English major of JRMSU is "competent," which shows that the respondents are competent in word formation (morphology), grammar (syntax), vocabulary (lexis), pronunciation (phonology), and spelling ability.

The finding of this study is supported by the study of Lasala (2014), which found that the level of communication in the oral and writing skills of senior secondary students is acceptable. Still, they differ in numerical values since their grammatical competence average in oral skills is 3.10. In contrast, they obtained an average rate of 2.91 in writing skills. Meanwhile, Cortez's (2016) analysis of intervention materials in producing Grade 7 grammar skills contradicts the findings of this study. Lasala's (2014) research, like Cortez's (2016), found that the level of competence of Grade 7 graduates in English grammar is only fairly competent. He concluded that the students had not developed adequate and necessary skills to master.

Meanwhile, the study of Cortez (2016) on the intervention materials in developing grammatical competence of Grade 7 students opposes the findings of the present study and Lasala’s (2014) research, as Cortez (2016) found that the level of competence of Grade 7 students in English grammar is only fairly competent. He concluded that the students had not developed adequate and needed skills to master the different grammar structures.

Table 2

Test on the Relationship between the Language Learning Strategies and Grammatical Competency Level of the JRMSU BSED-English Major Students

|

Variable |

Mean |

SD |

Spearman’s Rho Coefficient |

P-value @ 0.05 level of significance |

Interpretation |

|

Language Learning Strategies |

3.74 |

0.6090 |

0.9967 |

0.0000 |

Highly Significant |

|

Grammatical Competency Level |

81.09 |

7.6439 |

Table 2 presents the correlation test between the language learning strategies and the grammatical competency level of the BSED-English major students. The results reveal Spearman's Rho coefficient of 0.9967 and a P-value of 0.0000, which is lower than the α0.05 level of significance that indicates a strong positive relationship between the language learning strategies mostly used by the students and their grammatical competency level. It means that the more they used a specific language learning strategy, the higher the level of their grammatical competence and vice versa. Therefore, the correlation indicates that the students who usually use language-learning strategies could be competent in grammatical competency tests. In this case, Ha, which states that there is a significant relationship between language learning strategies and grammatical competency level, is accepted.

This finding aligns with Cohen's (1998) study, which manifested the connection between grammar learning strategies and grammatical competence. He argues that strategies likely contribute to more grammatically accurate speech, and he claims that determining what grammatical features are needed is one of the steps learners follow when talking. Learning strategies can facilitate learning grammatical items by helping learners explicitly notice them, structure them into working, and automatize them through practice to be available for spontaneous use. Also, the study of O'Malley and Chamot (1990) indicates that more successful second language learners use language learning strategies more frequently and appropriately than less successful ones.

6.0 Conclusion and Recommendation

The JRMSU BSED-English major students usually used metacognitive strategies in learning the second language. Therefore, they are learners who can be considered to be independent learners since they utilize metacognition or thinking about thinking. In addition, the students also used social, cognitive, affective, and compensation strategies in engaging in learning the second language. With these, it can be inferred that these students employed various strategies in learning the second language. It is further concluded that the overall grammatical competency level of the students is competent.

Nevertheless, the students are competent in word formation and syntax if considered by component. In contrast, they are less competent in vocabulary, pronunciation, and spelling. Furthermore, the student's language learning strategy use significantly relates to their grammatical competency level. Hence, training in language learning strategies should always be part of every language classroom.

English teachers may be encouraged to utilize teaching strategies matching the language mentioned above learning strategies of the students, such as providing them an avenue for listening to the second language. Language teachers of JRMSU may still offer extra effort in their teaching. However, it is needed to raise their competency to a "much competent" or "highly competent," more specifically in spelling, pronunciation, and vocabulary. English teachers may expose language learners to different language learning strategies. So be it in the form of language learning strategy training for them to learn English more effectively. Language teachers may do away with teaching the language through memory sub-strategies except for learning vocabulary, definitions, and literary texts.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank everyone who contributed to this article.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest in the publication of this article.

References

Abraham, R. G., & Vann, R. J. (1987). Strategies of two language learners: A case study. In A. L. Wenden & J. Rubin (Eds.), Learner Strategies in Language Learning. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Akbarov, A. & Arslan, M. (2010). SLA implications to language learning strategies and pedagogy. In 2nd International Symposium on Sustainable Development. A Conference Paper, 14-20. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274080524/download

Al-Jarf, R. (2008). Phonological and orthographic problems in EFL college spelling. First Regional Conference on English Language Teaching and Literature (ELTL1) at Islamic Azad University, Iran.

Al-Qahtani, M. F. (2013). Relationship between English Language, Learning Strategies, Attitudes, Motivation, and Students’ Academic Achievement. Department of Health Information Management and Technology, University of Dammam, Saudi Arabia. http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=523e0914-667f-4f84-990b-3ff6e79eea55%40sessionmgr4006&vid=0&hid=4201

Arellano, M. D. C. (2017). Memory learning strategies in English as a Foreign Language in Vocational Studies. In Tendencias Pedagogicas N֯29, 229-248.

Bachelor of Secondary Education major in English [BSED-Eng.] (n.d.). http://www.courses.com.ph/bsed-bachelor-of-secondary-education-major-english-philippines/

Bailey, A. L., & Butler, F. A. (2007). A conceptual framework of academic English language for broad application to education. In A. Bailey (Ed.), The Language Demands of School: Putting Academic English to the Test. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Bialystok, E. (1981). The role of conscious strategies in second language proficiency. Modern Language Journal,pp. 65, 24–35. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.tb00949.x

Brown, D. (1987). Principles of Language Learning and Teaching. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Brown, C. L. (2007). Strategies for making social studies texts more comprehensible for English language learners. The Social Studies 98 (5), 185–188. tandfonline.com

Cabrejas-Penuelas, A. B. (2012). The compensation strategies of an advanced and less advanced language learner: A case study. In Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 2, 1341-1354. doi:10.4304/tpls.2.7.1341-1354.

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1, 1-47.

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1981). A Theoretical Framework for Communicative Competence. In Palmer, A., Groot, P., & Trosper, G. (Eds.), The contract validation of a test of communicative competence, 31-36.

Celce-Murcia, M. (1988). On directness in communicative language teaching. In TESOL Quarterly, 32(1), 116-119. doi:10.2307/3587905

Chamot, A. U., Barnhardt, S., El-Dinary, P., & Robbins, J. (1996). Methods for teaching-learning strategies in the foreign language classroom. In R. L. Oxford (Ed.) Language learning strategies around the world: Cross-cultural perspectives (175–188), Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai'i Press.

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, Sage.

Crystal, D. (2003). English as a global language, 2nd ed., UK, University Press, Cambridge.

Cohen, A. D. (1996). Strategies in Learning and Using a Second Language. Essex, U.K.: Longman.

Cohen, A. D. (1998). Strategies in Learning and Using a Second Language. Essex, U.K.:

Longman.

Cornwall, T. (2010). Benefits of Teaching Grammar: Teacher-2 teacher. http://www.speechwork.co.th

Cortez, R. A. (2016). Supplementary intervention material in developing grammatical competence of Grade 7 students. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School. Ilocos Sur Polytechnic State College.

Diaz-Rico, L. T. & Weed, K. Z. (2010). The cross-cultural, language, and academic development handbook: A complete K-12 reference guide (4th ed.) Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Debata, P. (2013). The importance of grammar in English Language Teaching – A reassessment. In Language in India, 13(5), 482–486.

El-Dakhs, D., & Mitchell, A. (2011). Spelling errors among EFL high school graduates. In The 4th Annual KSAALT Conference, a paper presented in Al Khobar, Prince Mohammed Bin Fahad University.

Ellis, R. (2006). Current issues in the teaching of grammar: An SLA perspective. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 83–107.

Francis, D. J. & Rivera, M. O. (2007). Principles underlying English language proficiency tests and academic accountability for ELLs. In Abedi, J. (Ed.) English Language Proficiency Assessment in the Nation: Current Status and Future Practice. School of Education, University of California, Davis.

Gaard, E. D. (n.d.). Critique/Classroom Implications on Grammatical Competence. Retrieved from https://slaencyclopediaf10.wikispaces.com/Grammatical+Competence+%28Michael+Canale+%26+Merrill+Swain%29

Gao, C. Z. (2001). Second Language learning and the teaching of grammar. Education, pp. 2, 326–336.

Grammar Test. Retrieved from http://esl.fis.edu/grammar/q7m/1.htm

Green, J., & Oxford, R. L. (1995). A closer look at learning strategies, L2 proficiency, and gender. TESOL Quarterly, 29, 261-297.

Hinkel, E., & Fotos, S. (2002). New Perspectives on Grammar Teaching in Second Language Classrooms. Mahwah, N.J.L: Erlbaum Associates.

Hong-Nam, K. & Leavell, A. G. (2006). Language learning strategy use of ESL students in an intensive English learning context. In Science Direct, 34(3), 399–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2006.02.002

Khamees, K. S. (2016). An evaluative study of memorization as a strategy for learning English. In International Journal of English Linguistics, 6(4), 248-259. DOI:10.5539/ijel.v6n4p248

Krashen, S. (1981). Second Language Acquisition and Second Language Learning. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Krashen, S. & Terrell, T. D. (1983). The Natural Approach: Language acquisition in the classroom. London: Prentice-Hall Europe.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (1991). Language-learning tasks: Teacher intention and learner interpretation. ELT Journal, 45(2), 98-107. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/45.2.98

Lasala, C. B. (2014). Communicative competence of senior secondary students: language instructional pocket. In Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 134, 226-237. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.243

Liboon, Jr., A., & Rodriguez, E. (2017). Teaching Deficiencies of Teacher-Education Graduates of JRMSU-TC Based on the DepEd Criteria for Hiring Teachers. JPAIR Institutional Research, 10(1), 14-28. https://doi.org/10.7719/irj.v10i1.529

Lightbown, P., & Spada, N. (2006). How Languages are Learned (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Liu (2003). EFL proficiency, gender, and language learning strategy use among a group of Chinese technological institute English majors. ARECLS E-Journal, 1. http://www.ecls.ncl.ac.uk

Lyster, R. (1996). Question forms, conditionals, and second-person pronouns used by adolescent native speakers across two levels of formality in written and spoken French. The Modern Language Journal, pp. 80, 165–182.

Margolis, D. P. (2001). Compensation Strategies by Korean Students. In The PAC Journal, 1(1), 163-174.

McLaughlin, B., Rossman, T., & McLeod, B. (1983). Second language learning: An information-processing perspective. Language Learning, pp. 33, 135–158.

Millrood, R. (2014). Cognitive models of grammatical competence of students. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, pp. 154, 259–261.

Mohamed, A. R., Ismail, S. A. M. M., & Eng, L. S. (n.d.). Now everyone can measure grammar ability through the use of a grammar assessment system. In International Journal of Teaching and Education, 2(3), 127–136.

Muncie, J. (2002). Finding a place for grammar in EFL composition classes. ELT Journal, 56(2), 180–186. Oxford University Press.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2005). National Assessment of Educational Progress, 2005, reading assessments. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. In Abedi, J. (Ed.) English Language Proficiency Assessment in the Nation: Current Status and Future Practice. School of Education, University of California, Davis.

Nassaji, H., & Fotos, S. (2011). Teaching Grammar in Second Language Classrooms: Integrating Form-Focused Instruction in Communicative Context. New York: Routledge Press.

Nunan, D. (1991). Communicative tasks and the language curriculum. TESOL Quarterly25(3), 279–295.

Nunan, D. (1998). Teaching grammar in context. ELT Journal, 52(2), 101-109. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/52.2.101

Olshtain, E. (1987). The acquisition of new word-formation processes in second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 9(2), 221–231. doi 10.1017/S0272263100000486

O’Malley, M., & Chamot, A. U. (1990). Learning strategies in second language acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oxford, R. L. (1989). The role of styles and strategies in second language learning. Retrieved from http://www.ericdigests.org/pre-9214/styles.htm

Oxford, R. (1990). Language Learning Strategies: What Every Teacher Should Know. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Oxford, R. (1990). Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL). Retrieved from http://homework.wtuc.edu.tw/sill.php

Oxford, R. (2003). Language learning styles and strategies: An overview. Retrieved from http://hyxy.nankai.edu.cn/jingpinke/buchongyuedu/learning%20strategies%20by%20Oxford.pdf

Oxford, R. & Crookall, D. (1989). Language learning strategies, the communicative approach, and their classroom implications. Foreign Language Annals,22(1), 29–30.

Oxford, R. L., & Burry-Stock, J. A. (1995). Assessing the use of language learning strategies worldwide with the ESL/EFL version of the strategy inventory for language learning (SILL). System, 23 (1), 1–23.

Pontarolo, L. (2013). The Role of Grammar in EFL Instruction: A Study on Secondary School Students and Teachers. Dissertation, Italy: University of Padova.

Pronunciation Test. https://www.proprofs.com/quiz-school/story.php?title=pronunciation-test

Pronunciation Test.https://www.proprofs.com/quiz-school/story.php?title=mtewodm5oqjaxk

Pronunciation Test.http://highered.mheducation.com/sites/0072982772/student_view0/part6/ten_reading_selections-999/multiple_choice_quiz_4.html

Ramirez, D.C. (2012). Higher English Proficiency Level among Secondary Students. https//:www.academia.edu.com

Richards, J., & Rodgers, T. (2001). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rubin, J. (1975). What the "good language learner" can teach us. TESOL Quarterly, pp. 41–51. Jstor.org

Salahshour, F., Sharifi, M., & Salahshour, N. (2012). The relationship between language learning strategy use, language proficiency level, and learner gender. In Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, pp. 70, 634–643. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.01.103

Scarcella, R. (2003). Academic English: A Conceptual Framework. UC Linguistic Minority Research Institute Technical Report 2003-1. In Abedi, J. (Ed.) English Language Proficiency Assessment in the Nation: Current Status and Future Practice. School of Education, University of California, Davis.

Skehan, P. (2009). Modeling second language performance: Integrating complexity, accuracy, fluency, and lexis. Applied Linguistics, 30(4), 510–532. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amp047

Spelling Test.http://www.businesswriting.com/cgi-bin/commonmisspelled.cgi

Su, M. M. (2005). A study of EFL technological and vocational college students’ language learning strategies and their self-perceived English proficiency. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 2, 44-56.

Swain, M. (1985). Communicative competence: Some roles of comprehensible input and comprehensible output in its development. In S. Gass & C. Madden (eds.), Input in Second Language Acquisition. Rowley, MA.: Newbury House.

Szyszka, M. (n.d.). Foreign language anxiety and self-perceived English pronunciation competence. In Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 1(2), 283–300.

The State Collegian (2017). The Official Student Publication of Jose Rizal Memorial State University – Tampilisan Campus.

Toit, S. D. & Kotze, G. (2009). Metacognitive strategies in teaching and learning mathematics. Pythagoras, 70, 57-67.

Vicenta, V. G. (2002). Grammar learning through strategy training: A classroom study on learning conditionals through metacognitive and cognitive strategy training. Universitat de Valencia Servei de Publications.

Vocabulary Test. http://www.english-grammar.at/worksheets/general-vocabulary/general-vocabulary-false-friends-1.pdf

Wenden A. L. & Rubin, J. (1987). Learner strategies in language learning. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Wharton, G. (2008). Language learning strategy use of Bilingual Foreign Language Learners in Singapore. In Language Learning, 50(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/0023-8333.00117.

White, C. J. (1993). A comparative study of metacognitive, cognitive, social, and affective strategy use in foreign language learning. Dissertation. Massey University.

Wong, C. Y. & Barrea-Marlys, M. (2012). The role of grammar in communicative language teaching: An exploration of second language teachers’ perceptions and classroom practices. Electronic Journal of Foreign Teaching, 9(1), 61–75.

Word Formation Test. http://www.english-grammar.at/online_exercises/word-formation/wf050-sentences.htm

Word Formation Test. http://www.english-grammar.at/online_exercises/word-formation/wf037- sentences.htm

Yaimin (2006). A Study of Language Learning Strategies of Elementary School Pupils at SDN 1 Bengkulu. Thesis. Department of Languages and Arts. Universitas Bengkulu.

Yang, F. C., & Wu, W. C. V. (2015). Using Mixed-Modality Learning Strategies via e-Learning for Second Language Vocabulary Acquisition. Educational Technology & Society, 18 (3), 309–322. http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=2c73f2fd-2e1d-40b1-a64d-16394d2c5c97%40sessionmgr4007&vid=0&hid=4201

Zhang, J. (2009). Necessity of grammar teaching. International Education Studies, 2(2), 184–187.

Zhou, Y. (2010). English language learning strategy used by Chinese senior high school students. In English Language Teaching, 3(4), 152–158. www.ccsenet.org/elt